Taking a tour around the city’s ‘other side’ with Mihalis Samolis.

“What you see today, the fact I can talk to you so easily, I gained this through acting: when you’ve got 200 people in front of you, waiting for you to utter the slightest sound, then you stop being scared.”

The man talking in front of me is not an actor.

At least, not a professional one. His name is Mihalis Samolis and he is a 60-year old homeless Athenian. He is also a vendor for Shedia (which means “raft” in Greek), the street magazine sold by the homeless and the people outside the margins of society.

We are standing in front of the National Theatre of Greece, in the centre of Athens, and Mihalis is proudly waxing lyrical on the way he has contributed – in his own, heartfelt way – in the institution’s long history.

So, whenever I despair, I come to the theatre – I watch a show, whether good or bad.

“Years ago, the area surrounding the National Theatre was ‘Drugs Central’. The building itself was falling apart. Then Nikos Kourkoulos [celebrated Greek actor of the 50s, 60s, and 70s] took over its administration, called in the police, found sponsors, restored the buildings,” he says, with obvious pride. Then he turns his gaze, full of paternal tenderness, to a group of 15-year old schoolchildren hanging from his every word, and adds:

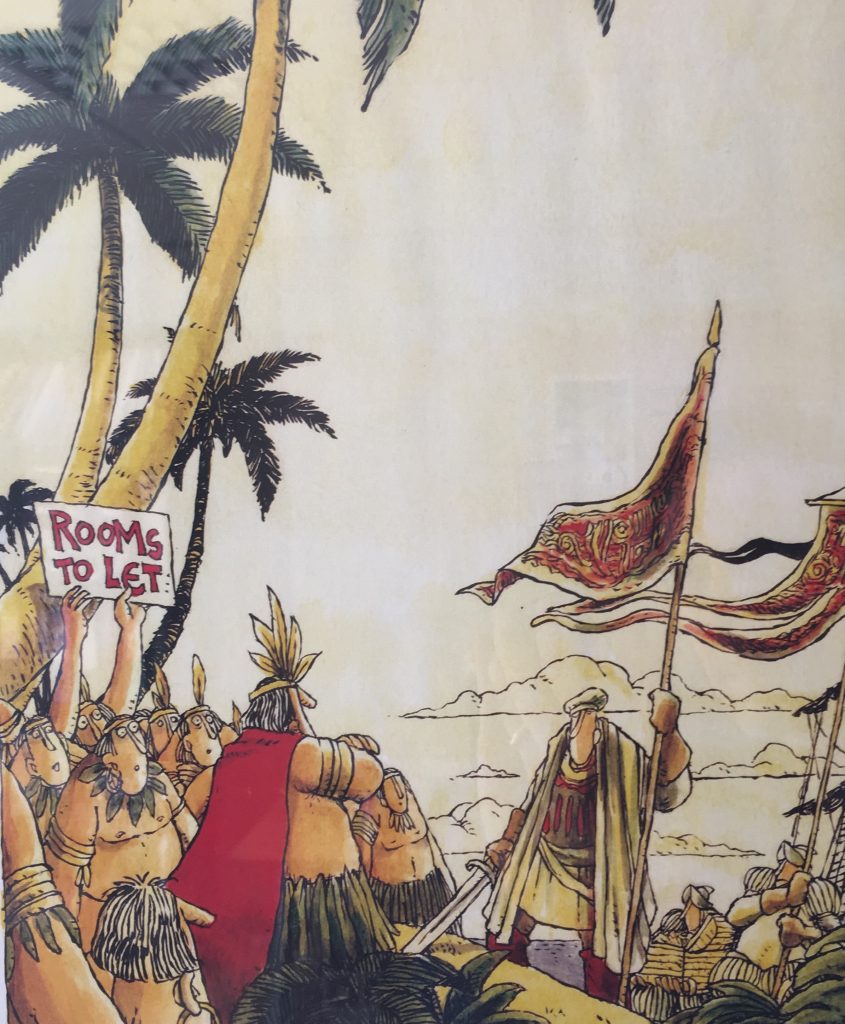

“You know, as a homeless person, I sometimes feel weird. We’re here now, talking, but at 8pm I have to go back to the municipal shelter where I have no place of my own, no room of my own, where I can’t sit down quietly, have a beer, watch TV by myself. I don’t have the quiet of a private space. This gets me down sometimes. So, whenever I despair, I come to the theatre – I watch a show, whether good or bad. It lifts me up. It makes me feel I’m human again.”

The shock of his brother’s death knocked Mihalis out.

Mihalis Samolis has been homeless for the past 6 years. Up until 2012 he was a thriving logistics entrepreneur, freelancing for big supermarket chains. He had his own truck. He grew up in the middle-class neighbourhood of Kallithea in 1957, nursing young boys’ dreams: a fascination for airplanes, trucks, and skyscrapers. As a young man, he managed to achieve all three: graduating from school in Greece, he left for New York, where he studied aerospace engineering.

He didn’t get to stay in the US long: he had to return to Greece to do his military service – a full 2 years of obligatory training, back then. He joined the Airforce. And when the 24 months were finally over, Mihalis had to choose between staying in the Airforce or joining his father and his brother in their removal and truck business. He chose the latter. It was a ready-made job and offered loads of pay.

Everything was going breezily, until one fateful morning in 2006.

“We wake up one morning, my brother and I, we have coffee, we load our two trucks, we plan out the logistics of the day. We were freelancing for a large, multinational company, transporting products from their warehouse to their super market outlets. Then I receive a call at 11 am: it’s my brother. ‘I don’t feel well,’ he says, ‘where are you?’ I tell him I’ll be there in half an hour. I set out in my truck to meet him. When I get there, I see his truck pulled over on the side of the road. I park, go up to it, open the door… he had fallen over the wheel, he was dead. Heart attack. The doctors said we were lucky: he had 4-5 minutes to pull the loaded truck to the side, so that nobody would get hurt. A 15-ton truck can pulverise a passenger car in an instant, even if it’s doing only 20 kilometres an hour.”

The shock of his brother’s death knocked Mihalis out. He was unable to work for months on end. He kept thinking it turn next. And then, within the space of a few months, he lost first his father and then his mother. He was left on his own. After all expenses and taxes were taken care of, he still had some money on the side: they had been a hard-working family. But then the money started thinning out and Mihalis returned to work, working his own truck. The company took him up again, immediately: he had been a valued associate. Things were starting to look up again. Until the Greek Debt Crisis hit in 2010.

But the final blow was yet to come.

I am listening to Mihalis’ personal story, together with the group of high-school kids, at Shedia’s head offices on Favierou St. Mihalis – apart from a Shedia vendor – is also the guide of a very special, educational walk around Athens, sponsored by Shedia: addressed to students, tourists, and Athenians who want to see ‘the other side’ of their own city, these walks are called Invisible Tours, and they are designed to communicate the reality of social exclusion in Athens (and Thessaloniki) today, to anyone who might care to listen.

During a 3-hour walk around the centre of Athens, the participants stand discreetly close to and learn about important social institutions operating in the city – from soup kitchens to shelters, from drop-in centres to mobile medical units. Such supporting structures have grown in size, importance, and demand during the years of the economic and refugee crisis.

The walk is a way to educate Athenians to notice and accept their fellow citizens who have been struck down by fate or wrong choices. It is a way for foreign visitors to discover that Greece is not only what they readily see (frappes in the sunshine and smiles in the middle of the day) or read about – the impersonal numbers in the news – but a whole new wave of nouveau-pauvres, who have been left homeless in the city where they were born and grew up in.

“Last summer I had groups of Members of the European Parliament come and visit and take the Invisible Tours,” Mihalis says. “And loads and loads of foreign visitors. They would come up to me and say, thank you, thank you for letting us know of what life is really like. They would have left the country not realising the deep problems Athens is dealing with. They would have left thinking that the Greeks are enjoying their lives in the sunshine and that there are no immigrants around. But none of this is true. The immigrants don’t frequent touristic places, you know. Most of them are here illegally and are scared to death the police might apprehend them.”

Yet the most important part of the tour is the personal stories of the vendor/guides themselves, of the men and women who bravely and generously share with you their personal battles, their slight victories and crushing defeats, their ever-lurking despair and never-dying hopes.

Mihalis’ story is a point at hand.

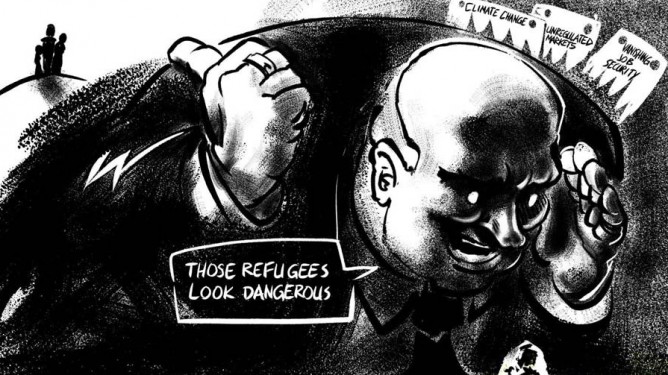

Returning to work after his brother’s and his parents’ deaths, Mihalis kept freelancing for the large multinational. Until the Greek government, due to the debt crisis, decided to “open up” the truckers’ regulated labour market. “You used to need 70,000 euros to get a license for a transport truck,” Mihalis says. “From 2010, these licenses were made redundant and jobs were completely deregulated.” Truck drivers went on a two-month strike. In the end, they were forfefully mobilized under a national emergency directive. “Saturday night, the police show up and present me with a paper saying I have to report Monday morning, with the truck full of gas, at work. Otherwise, I would go to jail.”

Banks were no longer giving out loans.

When Mihalis went back to work, the company asked him to lower his asking prices. They could now hire their own trucks and their own drivers to do their logistics work, and they needed a good motivation to keep him on as a freelancer. Mihalis reduced his charges by 40% overnight, losing – obviously – 40% of his income along the way.

But the final blow was yet to come.

It was an early morning in 2012. Mihalis woke up at 4:30 am, as usual, ready to go to work. He went out to his truck, but there was no truck there. It had been stolen. “For the first few days I was hopeful. I thought, where would you hide a 15-ton truck? It will be found, surely!” Six years now, not a single bolt has been recovered from his stolen vehicle.

Mihalis did not have 60,000 euros on the side to buy a new truck. Banks were no longer giving out loans. The money he had on the side where good to keep him going for a few months only. He started looking frantically for a job. But in a stagnated market where uner-30s unemployment is as high as 40%, “who would recruit me, with my white hair and all?”

I never go out without a hat on anymore. I take it off only when I eat.

Mihalis’ hair had been a constant joke when he was younger: it had turned white already in his early 20s. He used to laugh with his buddies about it. “But when I started looking for a job at 55, the first thing I noticed was how people were looking at my white hair, thinking he’s too old for this. I started feeling so bad about it, I never go out without a hat on anymore. I take it off only when I eat.”

Mihalis never found a job. The owner of the flat he had been leaving in had a right to kick him out after some months’ notice of unpaid rents. So Mihalis sold all his furniture for next to nothing, gave away half his clothes, threw the rest out, put his entire life in 6 cardboard boxes, stored them in a friend’s basement – where they still are today – shoved a few trousers, some underwear, and a couple of shirts in a suitcase, and took to the streets.

Today, Mihalis leaves in a homeless shelter that belongs to the Municipality of Athens. We are now standing opposite this very building, as discreetly as possible. “This is my home!” he says. It is the old Ionis Hotel, on Chalkokondyli Street, a 5-minute walk from Omonia square, the National Theatre, and the National Archaeological Museum. The shelter operates 24 hours a day. It accommodates 140 people, 20 of which are women and 7 of which are kids. The oldest tenant is 94 years old. “Do you see anywhere saying shelter? Nope. That’s why we call them ‘Invisible Tours’,” smiles Mihalis.

When the hotel was closed due to financial troubles some years ago, the City of Athens approached the owner and offered him money to turn the building into a homeless centre, unstaffed. The owner consented: now there are men and women taking care of it, repairing it, being grateful they have a place to stay. “If Athens ever gets out of this mess,” says Mihalis, “and the owner wants to re-operate his business, he very well can. He won’t be needing much money either; we have been taking good care of it. It’s a win-win situation.”

Mihalis shares a room with a younger man. He has a closet to himself, where he can store his few belongings, and is deeply grateful he doesn’t have to use some of the night shelters, where people sleep in large dorms and have to completely vacate the facilities each morning at 9am.

We bump into yet another abandoned hotel.

The students ask him how one can qualify for a place in such 24-hour shelters. “You must have no income, no property whatsoever to your name, and you must have passed all medical tests for HIV, hepatitis, dermatological, and psychiatric illnesses with flying colours. You also need to be able to be self-served, to take care of yourself.” The children protest. “There are other shelters for people who cannot take care of themselves!” fights back Mihalis. “Or for people who are ill, or HIV+. This is an unstaffed shelter. There are no nurses or doctors or cleaners here. We do everything by ourselves. Like in a cooperative.”

“Listen,” says Mihalis a few seconds later, turning serious. “This is a shelter. It is not a hotel. There are rules and regulations. Whoever does not feel comfortable with them, can go sleep underneath the many-starred sky. Do you know how many people actually choose to do so? When the rules say you can’t smoke in your room if your roommate does not smoke; when they say that alcohol and drugs are forbidden; when they say that the doors lock every night at midnight – and you try to break them more than once, you’re good to go. You have to sign a paper when you are first brought here, saying you will not break the rules. My personal opinion is that the people you see sleeping rough do not want to follow the rules. Do you know how many shelters there are available around?!”

Mihalis did not find a place in a shelter immediately.

We walk towards Menandrou street. We bump into yet another abandoned hotel. “The owner of this place would rather lock it up rather than allow the City to turn it into a homeless shelter. Look at it! It’s like a fortress. The only thing he hasn’t employed to keep people away is electrified barbed wires,” he says with a chuckle. Then he rethinks: “He does have a point, though. Once people get into an empty property here, the police have no easy means of removing them. The law is very lenient on squatters. But what a shame, huh? To leave buildings to themselves, to fall apart, empty and abandoned…”

Mihalis did not find a place in a shelter immediately. The truth is, he had no idea about all the public, municipal, local, or private organisations running free-for-all services throughout the city. He did not know about the soup kitchens – offered by the City or by all sorts of religious institutions; he did not know about the mobile medical units going around town; he did not know about the shelters, the drop-in centres, the places one can rest, whether run by the City, or the Greek church, or the Red Cross, or Caritas, or other NGOs. He had no idea how many support mechanisms operate every day, trying to help people who have fallen off society’s radar.

“During my first days on the streets, I made a decision: I said, that’s that then, I have to kill myself. I had no idea the things I am showing you today existed. I had no idea where to go to ask for help.”

“Do you know what saved my life? The fact that I couldn’t stand the pain. I started looking for a way to kill myself that would not involve pain. I couldn’t jump in front of an oncoming train. I couldn’t jump off of the 6th floor of a building. That would hurt too much.”

He left behind a thriving career in order to set up and run Greece’s only street magazine.

Hour by hour, days kept going by and his despair started lifting. Then one day, he happened upon the office of an NGO called Klimaka, which specialises in offering psychiatric and psychological services to marginalised individuals and implements social integration programs for vulnerable population groups. “As soon as they learnt of my situation, they set out to help me. They told me about the shelters and the hostels and the existing social support structures, and they recommended me to KYADA (The City of Athens Homeless Foundation) and KYADA sent me to the shelter I live in now.”

“When I first came to the shelter, I finally had a bed and some warm food to eat, but I only had 50 cents in my pockets. Then I met my friends Lambros and Maria. I kept seeing them eating souvlakia and pizzas night after night and I asked them where they got the money to eat non-shelter food. It was they who introduced me to Shedia. They were both vendors. And from the moment I stepped into the Shedia offices, my entire life changed for the better.”

Shedia vendors can be homeless, long-term unemployed, in general people who live and survive deep below the poverty line. There are vendors who used to live on benches and now have moved into shelters, or even cheap, rented apartments. “There are even some who live in their own, privately-owned homes,” says Christos Alefantis, journalist, and head editor of the paper. “But they have no electricity or running water. They sell Shedia in order to be able to save money to reconnect their utilities.”

Alefantis has been a journalist for the past 28 years. He left behind a thriving career in order to set up and run Greece’s only street magazine, and the side-projects it supports: vendor-made furniture created out of recycled magazines, or the National Homeless Football team of Greece. “Football-wise, we’re crap,” Alefantis admits laughingly. “But we’ve earned the Fair Play title more than any other team in the World Championships! That’s the highest honour a team can get!”

This soup kitchen is run by the municipality. Up until recently, it would operate once a day. Now it only serves food once.

Up until the end of 2017, the magazine used to cost 3 euros, 1.5 of which would go directly to the vendor. Due to a new law that obligates all freelancers to pay for their own social security, vendors now have to hand in 50% of their income for VAT and social security. “So we upped the price to 4 euros,” says Alefantis. “2 euros go towards VAT and social security, and 2 euros go into the vendors’ pockets.”

We are a bit taken aback that the Greek state would ask for VAT from a charity such as Shedia, let alone from people under the poverty line, such as its vendors. Mihalis is very concerned about this new turn of events: he sees his colleagues being really anxious about the sales figures, which are already starting to drop sharply. Is it possible a single euro can make such a big difference? “Why do you underestimate the value of a single euro?” Mihalis admonishes me. “The people who buy our magazine are not rich. They are struggling like me, like everyone. A euro’s difference might be too much for them.”

Alefantis tries to lighten the atmosphere, back in the office. “Look, the most important thing – more important than money, still – is talking to the vendors. Wishing them a good day.” He then urges the students: “Even if you do not want to buy the magazine, go ahead, say kalimera! Having people talk to you makes one feel good about themselves. The hardest part about poverty is not poverty; it’s social exclusion.”

Mihalis is back to his more cheerful self: “People don’t just offer a good word, you know. In the winter, they come up to me with cups of hot tea and chocolate. In the summer, I have a whole stack of bottled waters, juices, fizzy drinks behind me. People come and offer them to me with such joy, I can’t possible refuse! You can’t imagine what the support of these anonymous people has meant to me. When you become homeless, you first lose your shelter, then your food. And then, love. I used to think that shelter and food were the most important, but I have discovered that it is love. That’s what I’ve missed the most.”

A colleague of his chimes in: “When people engage with you, you become visible. You exist.” At Christmas time, he managed to go visit his sister for the first time after many years on the streets. “I even had a box of chocolates with me, as a Christmas gift!” he says, his face glowing.

This Crisis has not only rushed in unemployment and poverty.

We are by now standing at the south end of Sofokleous street, named after ancient Greece’s renowned tragedian Sophocles, and the old seat of the Athens Stock Exchange. The street is now a thriving node on the Athens drugs scene, a place for the illegal trafficking of stolen mobile phones and prostitution. Opposite us there is a huge queue of people waiting for the city’s largest soup kitchen to open

“This soup kitchen is run by the municipality. Up until recently, it would operate once a day. Now it only serves food once. Until 3 years ago you would get a main meal, 2-3 slices of bread, a small salad, a piece of fruit. All these began to be phased out, slowly, and now you get a main meal and some bread. In the beginning of the crisis, there would be private companies that came and handed out milk, juices, yoghurts. There was a “social grocery store” here. All this has stopped now. It’s been so many years into this crisis, and things get more difficult with every passing year.”

The City of Athens makes no distinction as to whom they serve. You can’t say the same for the Church of Greece – which, to render unto Ceasar the things that are Ceasar’s – has been helping people in all neighbourhoods of Athens, for the longest time. “The Church has fewer portions of food to offer, you know: 100 or so, when the City offers around 1,200 per day,” Mihalis says. “You also have to prove to them that you belong to their parish.”

I talk to kids who take sisa every day, I tell them it’s poison.

But there are other denominations that help despite one’s religious faith: the Evangelicals cook 2-3 times a week; the Buddhists too. The Catholic Church, through Caritas, provides food and shelter and a place to clean up. “There’s so much help from so many people. My personal opinion is,” and here he emphasizes that this does not reflect Shedia’s point of view in any way, “that there is no food shortage in Athens today. I know at least 10 places where I can go eat for free. I don’t know why there are people on the street who approach you and say I’m hungry… I’m hungry…”

Actually, he does:

“You know, this Crisis has not only rushed in unemployment and poverty. It has brought about a rise in criminality, prostitution, the proliferation of cheap drugs. There’s this pill making the rounds in Athens. It’s called ‘sisa’. It’s a little, white rock that people pulverise and inhale or inject. It’s pure poison. We took a couple of them to the General Chemical State Laboratory and were told they contained car battery acids, chlorine, whatever shit can be found cheaply on the market. Its effect is immediate and it lasts for 2 to 3 hours. Then you have to reload, so to speak. Do you know how much it costs? 1.5 euros.”

Mihalis stops and looks solemnly at the students. “Heroin, marijuana: they are ultimately derived from plant extracts, natural compounds. This is an entirely chemical compound, a really dirty drug. And it costs so little because you don’t need to import it or anything. All you need is a safe apartment and a couple of chemists that know how to ‘cook’, and you’re set.” 100% of sisa users die within a year of starting its use. The drug burns their insides, destroys their internal organs, turns them psychotic and extremely violent. “I talk to kids who take sisa every day, I tell them it’s poison. They agree. They know. Then they go and beg for some more. Then can’t quit. Nobody can quit this damn thing.”

Mihalis take a deeps breath. Pauses. Then smiles weakly. “But we were talking about soup kitchens, weren’t we? Well, as soup kitchens go, there’s always Kostas, aka The Other Person.”

The kids seem excited all of a sudden; they seem to have heard of Kostas before. “Kostas goes around Athens cooking and distributing food. I’ve known him for years. When he became unemployed, he started cooking on the street. In the beginning, no one would take his food. Then he thought of something: he took 3-4 of his colleagues and sat down to eat the food they had just made. Ever since then, people have been flocking to him like moths to the fire. Kostas figured out what hungry people really need: they need company. They want you to sit down with them, talk to them. So this is what he does. He cooks and then he sits down with people and he talks. For hours. Every day.”

One day we come by and we find them looted and set on fire.

A hundred feet away from the soup kitchen stands a 5-floor tall building, the headquarters of Medicins du Monde- Greece. Medicins du Monde provide what loads of Greeks – poor or not, homeless or not– cannot often find in the country’s state hospitals: medicines. “There are over 3 million uninsured people in Greece as we speak,” says Mihalis. [Greece a country of 10 million people]. “I was one of them until very recently, until social security was forcefully added to the hiked price of the magazine. In the shelter, we have people with cardiac problems, hypertension, diabetes, people who need drugs every day, throughout the day. Whatever we may need, we find it here.”

The City of Athens had recently built two small buildings opposite the Central Athens Food Market on Athinas street. One of them was a “Social Pharmacy”, handing out medicine to the marginalised. The other was “The Department of Clothing”, doing the same for clothes. “One day we come by and we find them looted and set on fire. The municipality abandoned the effort of restocking them after that. They repaired them structurally and left them empty. They transferred the Pharmacy and the Clothes Dept. near the central railway station, to a large plot the Army donated. But it’s too far,” says Mihalis.

The fact that the state and municipal mechanisms are more or less paralysed does not mean that people, as individuals, have lost their concept of solidarity: “I often sell Shedia by the metro station in front of Evangelismos Hospital. I just sit there and doctors come to me, inundating me with their business cards. GPs to cardiologists, neurologists to psychiatrists. They give them to me and say: take my card, come and see me! Whenever you need to, whatever you need.”

In a parallel street to ours stands the Red Cross shelter. Mihalis informs us that it provides bunk beds for 110 people, 60 of whom are children. “When I first saw these children playing happily together, I thought to myself they have no idea where they are, they think they are in a big playground. But the specialists assured me: they know exactly where they are and what’s happening to them. They simply do not want to talk about it.”

More and more people come to the shelters every day.

The Red Cross places a strict chronological limit on the families’ staying in its shelter. They make sure that, within 12 months, they’ve found work for at least of the parents, so that their children do not have to stay there longer. The program is overall successful: other candidates often relinquish their place for the sake of parents whose kids are in the shelter.

“More and more people come to the shelters every day, a suitcase in hand,” says Mihalis. “It’s a purely increasing trend, 8 years in this crisis. And we’re talking about some amazing people, often. I remember this man – he’s dead now, he was 80 years old back then – who had been an interpreter at the UN. He spoke 9 languages. A man would pass, he would talk to him in Arabic. A woman, he would converse with her in French. He would speak English with a third one…”

Mihalis pauses for a bit, seems to be thinking. Then says to the schoolkids and to us: “Never ever think that none of this can happen to you. Whatever happens to your neighbour can easily happen to yourselves.”

Our walk brings us now in front of the National Theatre, where this article started. Mihalis speaks with great affection about the theatre in general, and the role it played in his life as a homeless man. He tells us how he joined the KYADA theatrical team, how the director taught him how to love and appreciate the stage. How he used to perform in nursing homes, shelters, and hospitals until – the City not having any more money to support the team – Shedia took over its sponsorship.

This is Athenian reality today: life and death go hand in hand.

“We’ve even performed in the Athens and Epidaurus festival,” he smiles, speaking of the single most prestigious festival in all of Greece. “The last play I was in was called The Dinner. Five homeless Shedia vendors would sit down to dinner with 20 other audience members (who were, really, actors) and started, as if by chance, to recount their stories. I wasn’t one of the actors at the table, I was the waiter. But I got to hand out paper tissues and towels to the audience, who were crying like babies by the end of the play.”

We arrive at our next-to-last stop: it’s a drop-in centre supported by the NGO Praksis, on no. 26-29 Deligiorgi St. Here anyone can come and take a shower, have a cup of tea or coffee, eat something. There are accountants and lawyers present to help people out; there’s laundry facilities to wash your clothes. It’s all free. It doesn’t matter where you come from; it doesn’t matter how poor you are. You can be homeless or not, an immigrant, a refugee. Praksis maintains 3 more such drop-in centres and two health micro-clinics, one in Athens, one in Thessaloniki.

“Five years ago, when I first came to Praksis, you would knock on the door and proceed upstairs immediately. I used to bring my clothes to get washed here. Now I take them to a private laundromat. But due to the large number of people seeking Praksis’ services, you now need to make an appointment even to have a cup of coffee!” says Mihalis.

Praksis also has other ground-breaking programs for marginalised individuals: they often help out families where both parents are unemployed and under a state of eviction, by paying their rent for six months and finding them jobs; they send volunteers to the islands of Greece to help out with incoming immigrants and refugees. And here in Athens, they recruit volunteer female university students who live with unaccompanied minors of up to 10 years old, until a final solution is reached concerning their immigrant or refugee status.

Our final stop is the Central Athens Food Market, aka “Varvakeios Agora”. One of Athens’ most lively hotspots.

We come to a rest at a piazza opposite the market, right next to those two small buildings that the City had built for the Social Pharmacy and the Clothes Dept. and now stand locked and abandoned, surrounded by frightened, struggling drug users in plain daylight. This is Athenian reality today: life and death go hand in hand.

Happiness is right there, in front of your eyes.

“You probably didn’t see them as we were walking here,” says Mihalis, not forgetting he is addressing an audience of mostly 15-year-olds.

“But I saw them, they were there.” Who? “Prostitutes,” he says. “By 8 o’clock in the evening Sofokleous St will be swarming with women from every imaginable place in the world. Their asking prices start from 20 euros and go down to 10 and sometimes even 5. The police have told us that out of the 700 brothels operating in this city, only one – one! – is licensed to do so. That means that only one has had a proper doctor that comes to make sure the working girls and the place is clean and illness-free, and safe.” He then fishes out some impressive numbers: the last statistics about prostitution and sexually transmitted diseases in Athens (drawn in 2012 – there haven’t been any studies since) suggest a 1500% increase in prostitution, HIV+, hepatitis, and other diseases.

And on that not-so-cheerful note, our Invisible Tour is over.

Mihalis looks at the students who surround him, somewhat confused, somewhat numb. “Hey,” he says tenderly and sits down to rest. “Listen to me.” He bids us to sit down too. “Schoolwork and exams and all this stuff is good, but I’ll tell you this: do things that make you happy. Do things that help others. Do things that combine both. And do it now. Not later. A person does not need much in order to be happy. Happiness is right there, in front of your eyes, you just can’t see it like I wasn’t able to see it for years on end.”

All these little things you have now? These are happiness.

Half talking to himself, half-orating, he talks of his colleague and friend Lambros, the other Invisible Tours guide: “Lambros and I are survivors. Not everyone can be survivors. If we fell off a plane in the middle of the jungle, Lambros and I would organize a network of vendors and write on banana leaves!” The children laugh. “Of the 140 people whom I live with in the shelter, only 4 of us sell Shedia, even though Shedia was designed with exactly this kind of people in mind. The rest do not want to show the world they are homeless, they are ashamed of who they’ve become.”

Then Mihalis turns, wisely, again to the virtues of frugality:

“That play we performed in the National Theatre ended with my character saying: now me and my friend Lambros will walk out of here and go and feast on a couple of souvlakia and a couple of beers and you know what? We’ll be kings! Not even the king himself can feel as well as we do. And that’s why I am telling you: you don’t have to go through what I’ve been through to discover how simple it is be joyful, how little you need to be happy. All these little things you have now? These are happiness. Not the many or the grand.”

How right he is.

Kommentarer