Thousands of Greek children were semi-illegally adopted from Greece to the United States after the war. Now Professor Gonda Van Steen has written a book about the unknown tragedy.

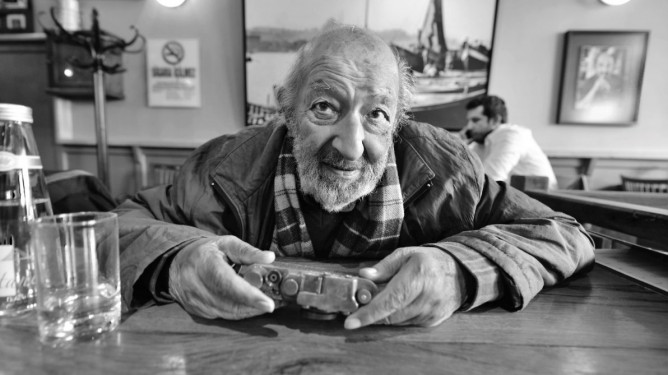

For the longest time, as is the case with most university professors, Belgian-American classicist Gonda Van Steen had been a shy academic researcher, spending time placidly pursuing her ‘ivory tower’ interests: researching classical drama and the reception of ancient and modern Greek language and literature.

Then one day, something happened—and it changed her entire outlook and focus in life.

Van Steen had no idea what he was talking about.

Van Steen was contacted by a young man from the Boston area who claimed that his Greek mother and aunt had been adopted by American families in the 50’s and asked if she could help him find serious scholarship on illegal adoptions from Greece to the US.

Van Steen had no idea what he was talking about. She knew of two kinds of massive evacuations of children in late 1940s through early 1950s Greece: a pro-Communist one, whereby 20-28,000 children were whisked off to countries of the Eastern bloc after the defeat of the Communists in the 1946-1949 Greek Civil War; and an anti-Communist counter-measure, whereby 15,000 or so children were removed from villages around the country and sent to “children’s towns”, as a means of stopping their being ‘abducted’ and sent behind the Iron Curtain.

The pro-communist παιδομάζωμα (‘pedomazoma’ / child-gathering) and the anti-communist παιδοφύλαγμα (‘pedofilagma’ / child-guarding) have received extensive historiographic treatment in Greek academic circles—and are heatedly debated. But sending children en masse to the US? There was certainly no available bibliography on that. Thinking that where there’s smoke, there’s fire, Van Steen decided to investigate.

Her first move was instinctive: she went online and typed Illegal Greek adoptions in the US. She found a series of contrasting and contradicting blog entries and opinion pieces that were inundated with discrepancies. Some attested that such adoptions never happened; others that there were tens of thousands of children involved in some sort of illegal trafficking between Greece and the US in the 1950s.

You have to try to picture it: by 1950, Greece was a scarred land.

“It was important for me to be accurate and discover facts and start a dialogue about this phenomenon” says Gonda Van Steen when we meet in Athens. After 6 years of extensive archival research and collection of oral histories, she has managed to confirm that a whopping 3,200 Greek children—from infants to 14-year-old kids— were adopted out legally, semi-legally, or illegally to the US (and a further 600 to the Netherlands) between 1950 and 1962. She was now back in Greece to give a lecture on her forthcoming book on the subject, “Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid Pro Quo?”

“It’s important to establish the numbers of these adopted children by checking against the discovered logistics: visas issued, flights booked, US admission documents. It’s also important to trace out the nuances of illegality. Even in the most illegal cases, there are certain aspects of the adoptions that are still legal: in the vast majority of the cases there are legal passports, legal adoption decrees, legal transport documents from the ports of Athens and Thessaloniki. But the circumstances of leaving Greece or the circumstance of arriving to America were certainly not pretty.”

You have to try to picture it: by 1950, Greece was a scarred land, a nation in ruins. It had just come out of a devastating civil war, which was essentially the first act in the global Cold War: already antagonizing each other since 1943, the communist and non-communist factions of the Greek resistance against Nazi occupation had turned viciously upon each other in March 1946, in what was to become the deadliest conflict in modern Greek history.

Both communist and anti-communist gangs roamed the country, killing—at the slightest excuse—anyone who was deemed to be a threat or a ‘traitor’ to their respective cause. Whole villages were annihilated; certain towns were communist in the morning, anti-communist at night, so to speak, depending on which troops took control of the area. Children were frequently sent away, in order to avoid the path of the advancing troops or guerilla soldiers. Often, which side you ended up on (and hence your future fate) was a matter of sheer geographical chance: my mother’s older cousin was removed to Hungary when our village in Epirus found itself behind communist lines; his father, stranded in Athens, remained loyal to the anti-communist Greek state army.

The need to shelter illegitimate, rejected, or orphaned children was enormous.

By the time Stalin split ranks with Tito, condemning Yugoslav support to the Greek communists, and Tito closed off the border with Greece in 1949, the communist partisans were in tatters. The end of the civil war and the massive amounts of military and economic funding Greece received from the US via the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan, helped the country undergo an incredible financial—but far more limited societal—recovery; a ‘miracle of reconstruction’, some might say.

1950s ‘Reconstruction’ Greece is habitually looked upon with a kind of myopic nostalgia which leaves out the harsher societal aspects of the time: defeated communist fighters and supporters were jailed or exiled for years in unforgivingly harsh conditions, on the country’s remotest islands; social taboos were strong; the illegitimate children of single mothers had no place in the conservative Greek society of the time; extreme poverty prevented thousands of families from holding onto their offspring; young kids were sent away to cities to work in the homes of richer families; babies as young as a few weeks’ old were left abandoned on the steps of churches, state institutions, or hospitals.

It was the McCarthy era.

The need to shelter illegitimate, rejected, or orphaned children was enormous. On the side wall of what is now Athens’ municipal art gallery (and, back then, the city’s primary municipal nursery) there was a sort of cupboard-like contraption in which babies could be left anonymously, to be taken in by the Greek state. In the early 1950s, more than 150 babies were abandoned in this baby chamber alone, every single year. This means almost one baby every other day.

At the same time, Greece was greatly dependent on American aid for its recovery. Gonda Van Steen sees her research as providing evidence towards how the need to place Greece’s foundlings in families, and the need for the country to receive massive amounts of US aid, were interconnected: “American demand for children at the time was huge. Greece quickly realized that offering her abandoned offspring was a manner of cooperating with the US.”

It was the McCarthy era. Americans were encouraged to fight against communism by building strong, conservative, traditional families. “We are talking baby-boom times. The prevailing slogan was a nuclear family for nuclear times” says Van Steen. Had you no children and no capacity to have any, you adopted.

Yet the language stuck because it was the language of humanitarian rescue.

As domestic supply started falling short of demand, Americans started looking to adopt abroad: to Germany, Japan, Korea, Greece. “The sales pitch” says Van Steen “was that children from those countries were ‘war orphans’, children that needed to be rescued. This might have applied during the 1940s and the early 1950s for Greece, but by 1962 it was an outright lie. Yet the language stuck because it was the language of humanitarian rescue.”

“In a manner” she adds, “tracing the stories of these 3,200 children adoptees is my way of questioning 1950s Greece, questioning all that massive American aid: who it was meant for, who it was not meant for. […] Greece craved American investment and financial aid, and so I understand that the Greek governments of the time had decided not to impede the export of children to the US. They weren’t actively behind it—there were lawyers, orphanage directors, doctors who were directly involved and so directly responsible for this commercial exchange, for there was money involved, for sure. But I have come to think that sending these children to America was an instance of Cold War politics. America was on the demand side, Greece on the supply side. America invested money, sent people over to help; it wanted something back, without much ado. And this something was children. Within the framework of the Cold War, we can say that these Greek children became a bargaining chip.”

Most of the 3,200 babies and children that left Greece to travel to the US between 1950 and 1962 came from the municipal nursery of Patras, the great port town of western Greece, from which freighters and passenger vessels leave for Italy and beyond. “In Patras the nursery administration was very willing to collaborate with the mediators” says Van Steen. By 1953, when the Refugee Relief Act became a watershed in American immigration policy, making visas and passports easily available, a constant stream of children leaving Greece on commercial TWA and Swissair flights would be established.

Because they are white. And this is 1950s America.

“These trips took 2 to 3 days to be completed: from Athens to Switzerland to Canada to the US. Very often, the very first memories of these children are of the long and arduous, disorienting flights.” Adoptees were also flown to the US in specially modified cargo planes belonging to the Flying Tiger cargo company, who could bring in as much as 70 passengers at a time, turning the whole thing into a publicity stunt. American newspapers of the time baptized such flights ‘baby airlifts’.

“I want to stress that this flow of children to the US is entirely dependent on American policies” clarifies Van Steen. “The need in Greece was high but that doesn’t mean that the country could increase the number of children it sent abroad by itself. The adoptees could only go to America when America opened its doors.”

The kids were placed in middle- or upper-class American families. Poor families couldn’t afford them and black families were not even considered for adoption. A lot of Greek-American families applied and got their own little baby from Greece. A lot of military families too; they’d travelled abroad and met children from other cultures and were happy to take in non-American kids. “And yet, think about it: in a huge pool of supply made up of Korean, Japanese, and Greek kids, the Greeks are the first to be adopted. Why?

How did prospective parents learn about and apply for these adoption?

Because they are white. And this is 1950s America. We would love to adopt a Korean child, a couple in a small town in North Dakota might say, but it would be difficult. But a Greek child? Yes, please.” A lot of Jewish families adopted Greek kids too. The reason is as self-explanatory as it is surprising: since most Jewish children had been eliminated in the Nazi death camps, there were hardly any Jewish babies available domestically in the US. American Jews often turned to Greek children, then, as they fit, ethnically and racially, their idea of what a Jewish kid would look like.

How did prospective parents learn about and apply for these adoption? “Through the grapevine! Once a child was adopted, other couples in the area would learn about it via word of mouth and apply as well.” The one good thing about this practice was that, since the parents were in contact, the children could keep in contact too. “To this day, one of the driving factors behind adoptees looking for their birth families in Greece is that they are also looking for each other.”

I ask Van Steen about the criteria on which these target families were judged. She shakes her head. “They had to give proof of sufficient finances and they had to be properly married, but that’s about the only info they had to provide—which says nothing about the strength or psychological capacity of those families to receive children.” A lot of Americans petitioned for Greek children after they had been rejected for domestic adoptions by the social workers in the US. “Some of these families were really too troubled to receive a child” she adds, bitterly.

These adoptions are the first celebrity adoptions.

She tells me about father Spyridon Diavatis, from San Antonio, TX, a Greek Orthodox priest with no education or experience as a social worker, who single-handedly placed some 80-90 children in families spanning the whole southern Texas region (St. Antonio, Houston, Austin) without any checks other than financial ones. Children in those families have come forth to share stories of disillusionment, deception, and outright abuse. “I am perfectly willing to believe there were good adoptions and that those are not the ones talked about. But unfortunately, the tragic stories are pretty tragic” sighs Van Steen.

Some of the most unfortunate ones involve older children, who not only remembered that they once had a family back in Greece, but had the hardest time adapting to their new home: learning a second language from scratch, having their names changed to American ones or their religion switched overnight. Greek customs, stories, foods, words were wiped out in one go. “These children were supposed to have no history before arriving in the US” says Van Steen. “And if they did, it was the history of classical Greece”.

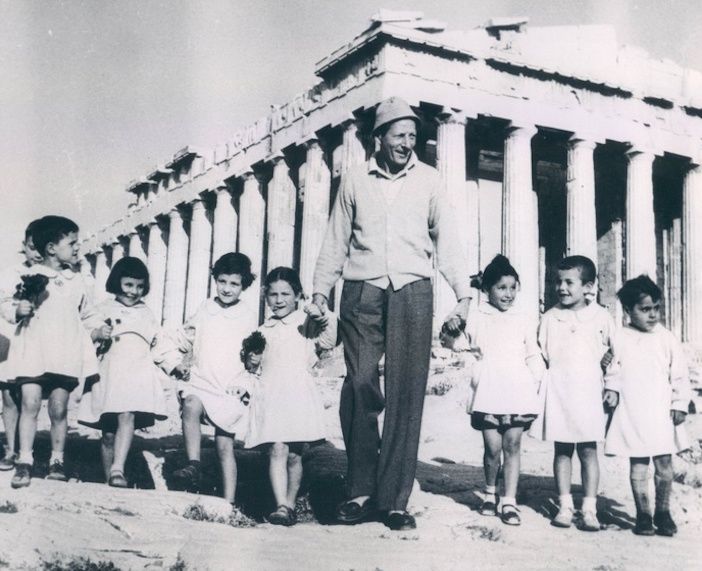

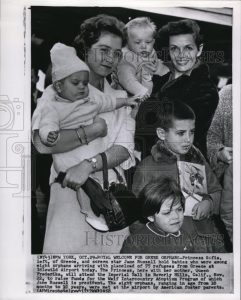

She shows me a picture of the actor Danny Kaye with a bunch of Greek orphans on top of the Acropolis. “These are celebrity pics. These adoptions are the first celebrity adoptions”. Other pictures show actress Jane Russell, Queen Frederica of Greece, and members of the International Social Service fundraising for the Mitera orphanage. The 600 kids that left Greece for the Netherlands were all from Mitera’s branches in Athens, Corfu and Crete.

Do they find their birth families?

“There was this little girl, nine years old. She was from Ouranoupolis and was taken to Los Angeles, to a family that was in no way fit to have children. She remembers being forced to eat raw meat. She remembers being molested. The parents had also adopted a little Greek boy, to whom she was not related; they weren’t allowed to speak Greek to each other. The little girl knew she had a family back in Greece. She didn’t get to see them again for 15 years. Once reunited, their broken relationship was never mended. The mother never got over the fact that she’d given her child away; and neither her siblings back in Greece, nor herself, think that her going to the US was anything less than a tragedy.”

The shift from the US to the Netherlands as the prime destination of Greek adoptees happened after the—infamous in Greece—Ayios Stylianos nursery scandal. “In the Ayios Stylianos case” explains Van Steen, “there were numerous documented confessions about how parents—of twins most often—were told that one of their babies had died in the hospital, shortly after birth. Only it hadn’t. Birth certificates were never issued, death certificates were never issued; these infants simply went missing.

Other babies whose mothers were known were reregistered as foundlings, to speed up the adoption procedures. It became a huge scandal and accusations started flying around that these infants were being illegally sold to the US. This shifted the weight towards the Netherlands, where adoptions were made under much stricter rules and better conditions.”

I ask Van Steen how it is that the, mostly American, adoptees decided to start searching for their birth families now, 60-70 years after having been adopted. “Some of them were told from the get-go that they were adopted; others were old enough to remember. Then, there are those from whom their adoption was kept a secret; there are people who got the shock of their lives when they found their adoption papers whilst clearing out their dead parents’ house, or when they did one of those popular DNA tests and found out they had a very larger percentage of Greek DNA.

But it seems to me that what drives most of them to look for their origins is some sort of a 60+ existential crisis, the death of a parent or a spouse say, or simply the fact that they have no true picture of their medical history now that they are getting older.”

I ask her to share a story with a happy ending.

Do they find their birth families? “It depends. If the adoption was legal and the child had been adopted via a court order here in Greece, then we can find out the mother’s name, and hence her father’s name, and we can work from there. If the child was born out of wedlock and came without a name and without a birth date, as a foundling, then it is very difficult. Sometimes these adoptees run ads in national and local Greek newspapers, or go to television shows, asking people if anyone knows who they truly are, if anyone recognizes them.”

The sources and archives in Greece are very disappointing when it comes to tracing orphans, foundlings, or even legally adopted children. In Greece, adoptions are handled with great confidentiality even to this day. Up until 1996, not even an adult adoptee could request and read their full file. “It is still very hard to get to the bottom of what happened. Not everyone is aware of the 1996 law change and not everyone is willing to help. On top of that, all material is protected by legal restrictions on personal information and these restrictions are only tightening up” explains Van Steen.

And yet, Van Steen looks passionately into everything that could mean anything. Often, mothers who abandoned their children in nurseries and orphanages left a note attached to their clothes, as a farewell letter to their child. The institutions kept these notes as an identifying feature, in case the mothers came back. Some children came with entire letters attached to them. And some mothers left notes asking for the children to be adopted, but also made a note of their real names. “I find this very honorable” says Van Steen.

For every adoptee looking for his/her family, there’s a family back in Greece looking for the child they handed over.

I ask her to share a story with a happy ending. “A friend of mine, for she has become a friend by now, found her birth mother in a remote village in central-west Greece after 59 whole years. Her adopted parents, in America, had been told by the middlemen that the mother had died. To the birth mother they said that her child had gone missing. The mother never had other children.

The daughter came looking from her, all the way from Tennessee, after 59 whole years. When they met, they embraced, trembling. One couldn’t speak English, the other couldn’t speak Greek. The mother, old as she was, did the most motherly of Greek things: she cooked for her child. And as they sat down to eat together for the first time, without being able to speak to each other, the old woman picked up a napkin and started lightly wiping her daughter’s lips, as if she were still that little baby girl who had been given away so long ago.”

To understand the magnitude of the phenomenon, you can compare Greek and Korean adoptee numbers sent to the US in the 1950s through 1962. From Korea: approximately 4,100 children; from Greece: 3,200. Only Korea had, at the time, 4 times the population of Greece. This means, shockingly, that proportionally speaking, the numbers of Greek children adopted out to the United States between 1950-1962 surpasses the numbers of Korean children sent to the US in the same time span. For most Greeks, this is a startling realization, especially since the Greek adoption history is unknown whereas the Korean history is not.

Her name is Despo. Please, she eats a lot.

“I often wonder” says Van Steen when we get up to leave, “why didn’t anyone ever ask the reverse question? If there was money to be spent on adopting Greek kids and bringing them to the US, then there must have been money to give to their birth families, their birth mothers, so that they could have stayed in Greece. Why didn’t we reinforce the welfare state in Greece? Or the foster parent system, so that, at some point these kids could have been reunited with their families? It was easier, I dare say, it was even public policy to put these children on the fast track to America, rather than look for more local solutions.”

It’s not like it wouldn’t have worked. For every adoptee looking for his/her family, there’s a family back in Greece looking for the child they handed over, or the child that went missing, or the child that was presumed dead. What parent gives away their child without a second thought?

Gonda Van Steen shows me a picture of a note found attached to a baby at the Patras Municipal Nursery. It reads, in Greek: “[She] was born on January 5, 1958. Her name is Despo. Please, she eats a lot.”

Gonda Van Steen’s Adoption, Memory, and Cold War Greece: Kid pro quo? will be available in December 2019, from the University of Michigan Press.

Kommentarer