– I am a reporter who prefers going to places others don’t like to go, says Coşkun Aral.

“The first shots sounded like they came from a hydraulic drill operating close by, but lightning reflex alerted my brain that my senses were being deceived. Something similar must have occurred in the same instant to thousands of people across the square. At first everything went quiet, but when the shooting resumed, there was desperate shouting and panicked flight in every direction: the herd was now stampeding. “They’re shooting!” someone called out. Several automatic weapons were fired simultaneoulsy. I was thrown forwards by a powerful push to my back. It was when that I began to feel genuine fear. I thought I had been hit. It turned out not to have been a bullet, but the people behind me trying to get past. I was caught up in the momentum and carried away. It was impossible to stand on my feet. I was a helpless victim of the pressure from behind, and I pushed those ahead of me in turn, unable to think of what else I could do. Suddenly a tall young man stopped in front of me, waving his arms in the air and shouting “Don’t panic, don’t run!” but he was instantly swallowed up by the stampede. I spotted through a tiny gap that we were close to Kazancılar, which slopes down towards Kabataş Quay. The hill was covered with fallen bodies piled on top of each other. I stumbled over a lifeless figure on the cobblestones, fell on all fours and hurt my knees. The pain shot through me, and together with the threat of the human wave behind me, triggered my survival instinct. I knew I had to do something or I would shortly be trampled to death.”

Little did I know some years ago, when I was translating these lines from Izzet Celasin’s award winning book “Black Sky, Black Sea” (MacLehose Press/ transl. Charlotte Barslund) into Greek, that I would one day meet the man who took some of the most iconic photos of that day: Turkish war correspondent and photojournalist Coşkun Aral.

Take your films, come to my office’ he says!

The events are known in Turkish as Kanlı 1. Mayis: Bloody May Day – the day the Turkish deep state shot and killed, or caused the deadly stampede of, more than 35 peaceful protesters on Taksim square. It was 1977. And the 21-year-old Coşkun Aral was about to get his first break as a big-time photographer of deadly conflicts.

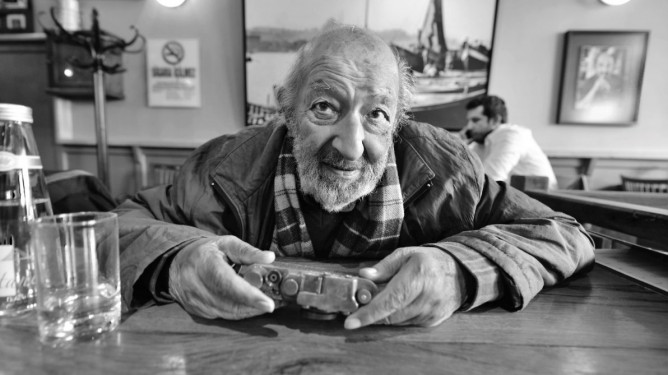

“I remember it clearly,” says Aral when I ask him about that day.

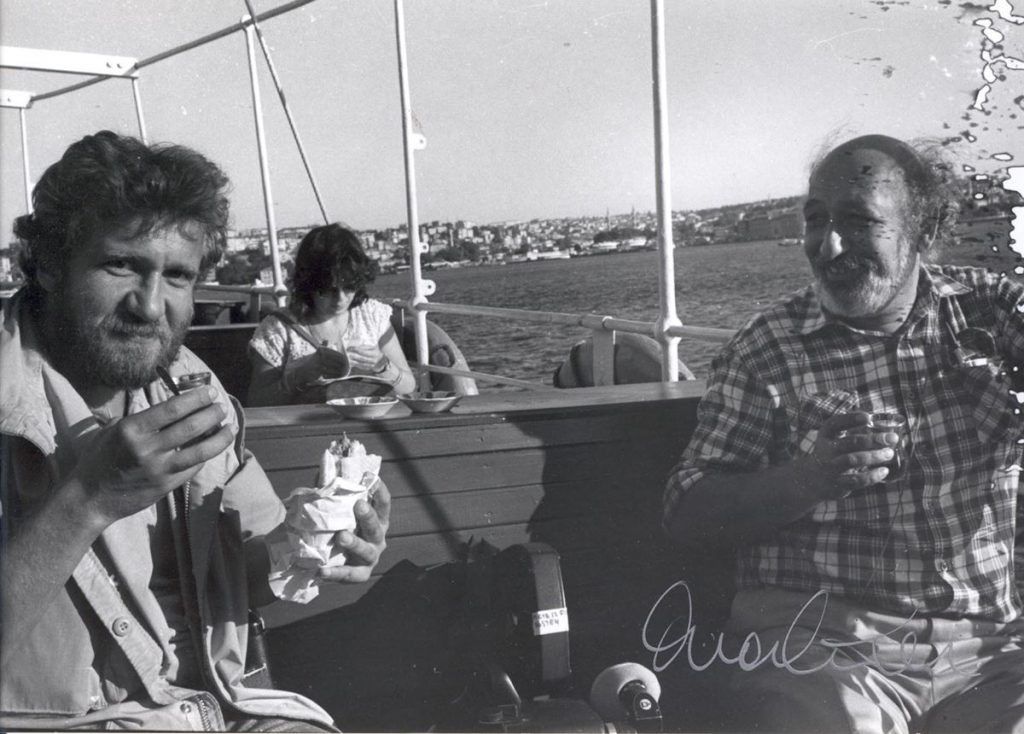

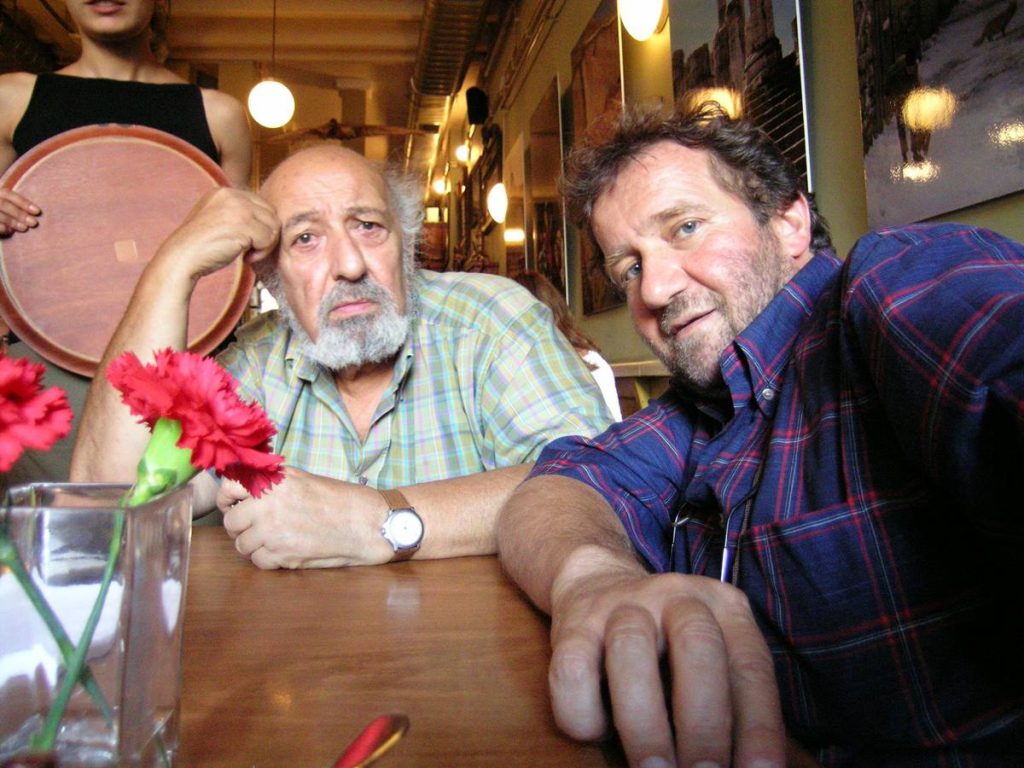

“There was this Turkish-Greek woman, Talia Dona, working for the Associated Press; she saw my pictures and she bought them straight away. Next day I receive a call from none other than Ara Güler. ‘Take your films, come to my office’ he says! He personally took my photographs to TIME Magazine, to Newsweek. After that I became the Turkish correspondent for the Paris-based SIPA agency.”

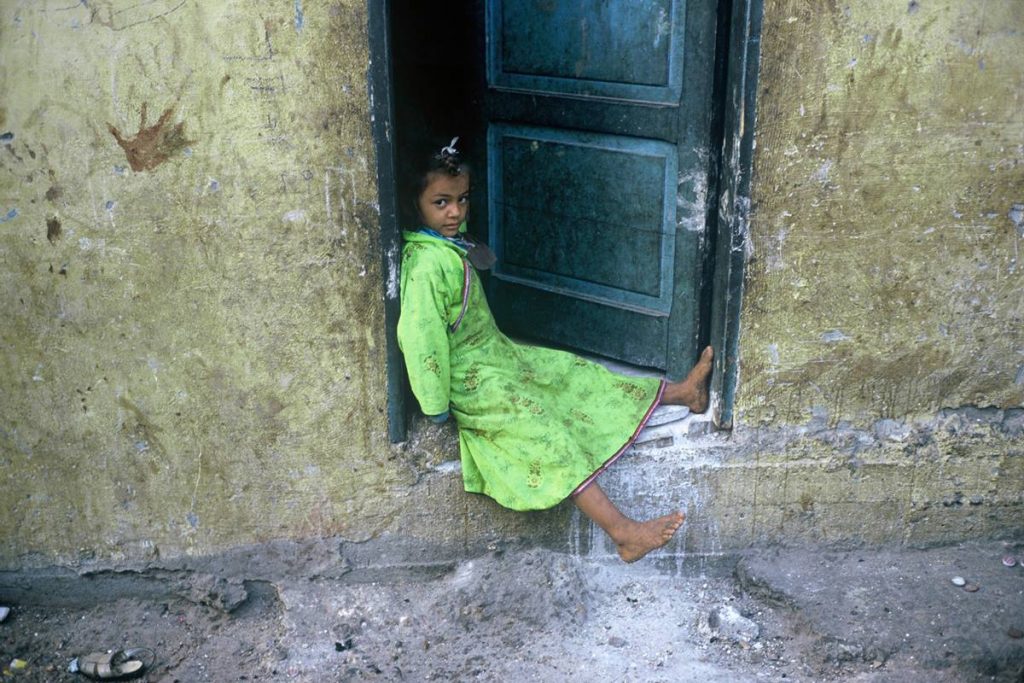

It may sound easy, but it certainly wasn’t so for a boy from Siirt, Mesopotamia, a town closer to Iraq and Syria than the capital of his own country. The area is a veritable melting pot of non-Turkish ethnicities: Kurdish, Arabic, Armenian.

“No journalist would come to our part of the country, we were the ends of the earth” recalls Aral.

“And then one day, when I was 10 years old or so, I see pictures of my hometown in the weekly glossy magazine Hayat (Life) signed by Ara Güler. That was it. I wanted to become a photographer-reporter ever since! And a doctor, of course.”

Siirt had no doctors, no hospital, nothing.

By the time the 1971 military coup occurred, Aral was 14 years old and many of his family members had been languishing in jail for years, imprisoned by right-wing administrations who venomously disliked strict secularists, supporters of the Kemalist party CHP, and leftists.

“By the time of the coup, I was already living in Istanbul. Siirt had no doctors, no hospital, nothing– so I’d left. I started writing small articles for my local newspaper, sending back photographs of youth protests in Istnabul against the military regime. I dreamt of becoming as famous as Ara Güler. I was 17 years old when I first met him. I panicked, it was a complete disaster!” he chuckles.

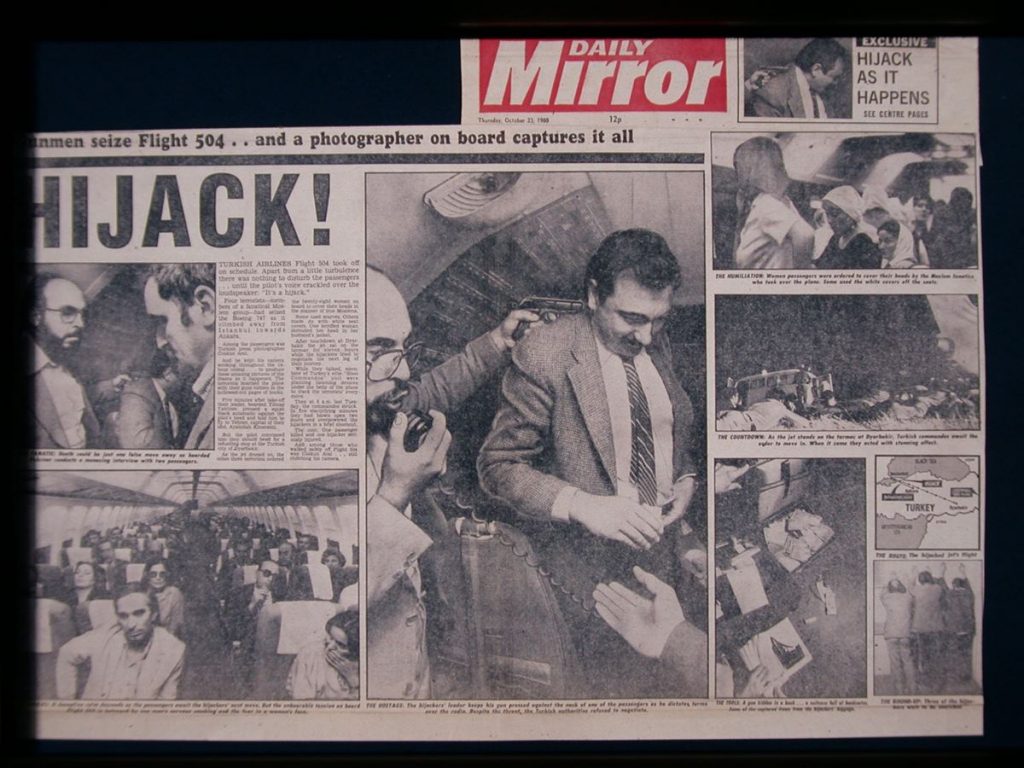

By the time the 1977 Bloody May Day took place, Turkey was in a complete state of chaos. Right-wing ultra-nationalists employed death squads against left-wing workers’ unions; the neo-fascist Grey Wolves, in political cahoots with the Islamist MSP party, were massacring leftist students and Alevi Muslims. On September 12, 1980, yet another military coup put an end to this tensed state of affairs. A month afterwards, on October 14, 1980, Turkish Airlines flight 504 from Istanbul to Ankara was hijacked by four Islamist extremists. And Coşkun Aral happened to be on board:

“It was the 17:35 flight and the aircraft’s name was Diyarbakır. It takes 40 minutes to get to Ankara but after an hour and a half, we still weren’t there. There were no announcements from the flight deck. Then suddenly we hear this voice saying ‘From now on, Islam commands the plane. Women passengers should cover their hair. If you have nothing to cover it with, use the headrest covers. We wish no harm to anyone onboard. We’re fighting against the military fascist regime.

We’ll take the plane to Iran and then to Afghanistan to fight with the mujahideen.’ I automatically took out my camera and started taking photos blindly. A man was walking down the aisle and, crazily, I asked him for an interview. He rejected my offer. But after a while, a bearded hijacker approached me and told me to follow him. I asked how they managed to smuggle the gun on board. He said they thought of carving a hole inside the Holy Quran, but it would have been a sin; so they found an Arabic dictionary without Turkish or Latin letters on the cover, and put the gun inside. I heard laughing from inside the cockpit. When I entered, everyone had a smile on their faces. The pilot had told the hijacker not to point the gun to his neck: he might be tickled and crash the plane.”

When I was growing up in Siirt in the 50s and the 60s, there was conflict all around us.

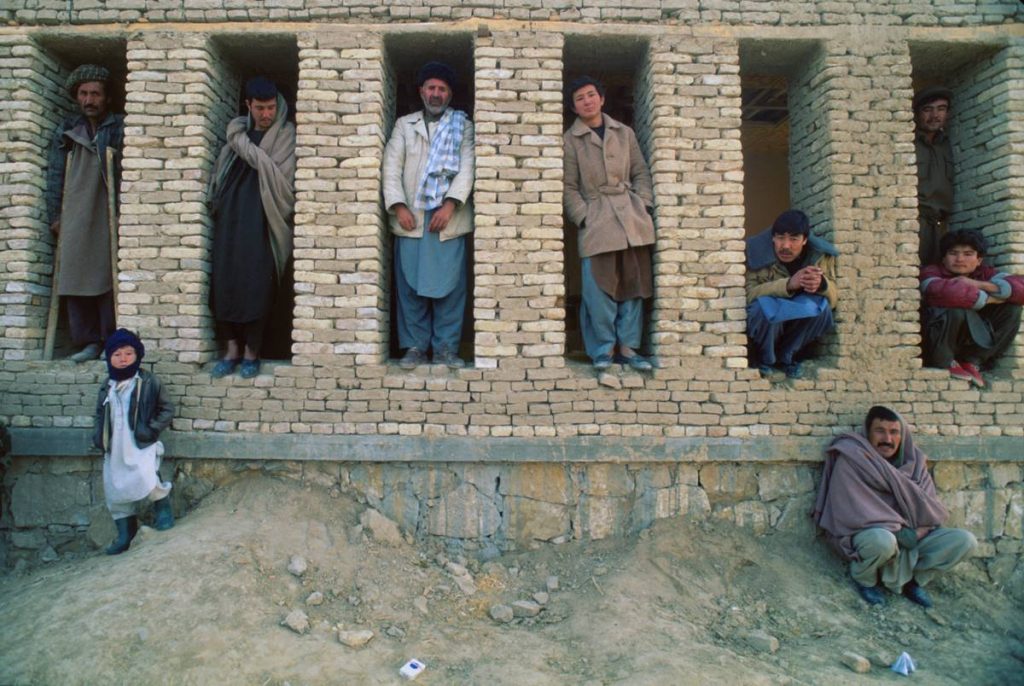

When the Turkish armed forces stormed the plane and put an end to this surreal hijacking, Coşkun was mistakenly arrested and held captive for four days in a Turkish prison. When he got out, the scoop brought him international fame. From then on, he worked in every conflict-ridden area in the world: Lebanon, Rwanda, Iran/Iraq, Northern Ireland, Liberia, Afghanistan, the Philippines, Nicaragua, Syria… His pictures are merciless, hardcore depictions of the insanity and brutality of war and civil conflicts. When I ask him what it is that has drawn him to such places, he simply says,

“I am reporter who prefers going to places others don’t like to go.”

But why?

“When I was growing up in Siirt in the 50s and the 60s, there was conflict all around us. We didn’t have the PKK then, but we did have revolts against the Turkish state. My part of the world has been riddled with conflict ever since the times of Alexander the Great, ever since Xenophon wrote his Anabasis. The distance from Siirt to Diyarbakir is only 200 kms. Yet by car it took us five hours to get there I was a kid: there were checkpoints every 50kms. Checkpoints. Inside the borders of my home country. So I started wondering about these things, asking questions from a very young age. I still like asking questions. Even better, I like searching for answers.”

One of the answers he’s come up with, when it comes to the destiny of his own mountainous homeland at least, is geographical determinism: “Hillside, mountainous people are more aggressive in my experience, than Aegean populations –say– who are mellow and nice. You go to Ara’s parts of the world, in Şebinkarahisar in northern Turkey, and you find a very bellicose kind of land.”

So geography is destiny?

“We attribute this quote to Ibn Khaldun very often in Turkey, but whosever it is, I think it is correct. I remember talking to Abdullah Öcalan [jailed founder of the Kurdish PKK] once and he confessed that he did not believe Kurds could ever build a free state unless local feudalism was defeated. He said he liked Atatürk. But he needed a way to convince Kurds to fight. How else was his going to get them out of bed every day?”

Feudalism in the 21st century?

Aral smiles.

“Revolts in Kurdish areas are simply a continuation of the people’s revolts throughout the old Ottoman lands. Serbs, Greeks, Arabs: they conducted wars of independence through revolts and rebellions. This is still going on today in the Kurdish areas of Turkey: there is a very peculiar state of feudalism at work there. There are feudal masters who control the votes, the taxes, the money, everything. Feudalism is the big enemy of the people, yet local lords keep their power due to geography: right outside Siirt, for example, there is a little town called Pervari. For 3 whole months during the winter time the town gets snowed in and nobody can access it.

I believed in Communism up until my thirties.

Nobody wants to go there. The central authorities cannot or do not want to send people over: they use the existing, feudal local networks to keep life going. The Dalai Lama said to me in person once, ‘We will never have freedom in Tibet because the geography makes it impossible. But I have to speak about liberation. The Tibetans need to believe in something.”

Do you believe in something? Do you still believe in the Left, for example? I ask him.

“No,” he says firmly. “I believed in Communism up until my thirties. I visited the USSR. But now I think it’s all a utopian construction. I don’t believe in socialism, communism, liberalism, any of these old ideologies. I believe in human beings. Ideologies are opportunistic. Look at Europe: you have human rights, you have democracy. And yet you still produce guns and the materials sold and used in chemical weapons. Switzerland is all about referenda, isn’t it? And yet they produce anti-personnel mines!”

Where do I start?

My instinctive reaction is to argue back that in all countries some people do good, some people do evil. But he’s one step ahead of me:

“You know, if you’ve seen war, you cannot say that these people are better and the others. When I was a leftist I kept asking why Kurdish people do not simply rise up to take power. But when I later saw the Left’s policies towards the Middle East I saw the exact same opportunism I had seen from others: you switch to the terminology of Marxism-Leninism only to have your friends and close ones benefit, while continuing to oppress the people.”

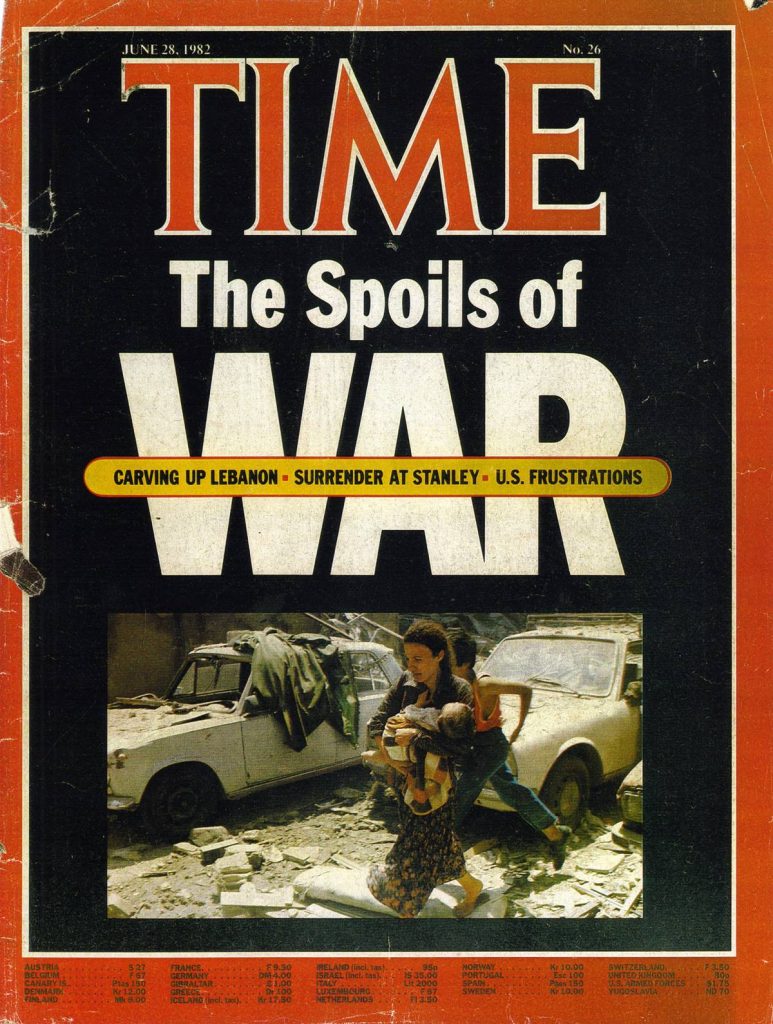

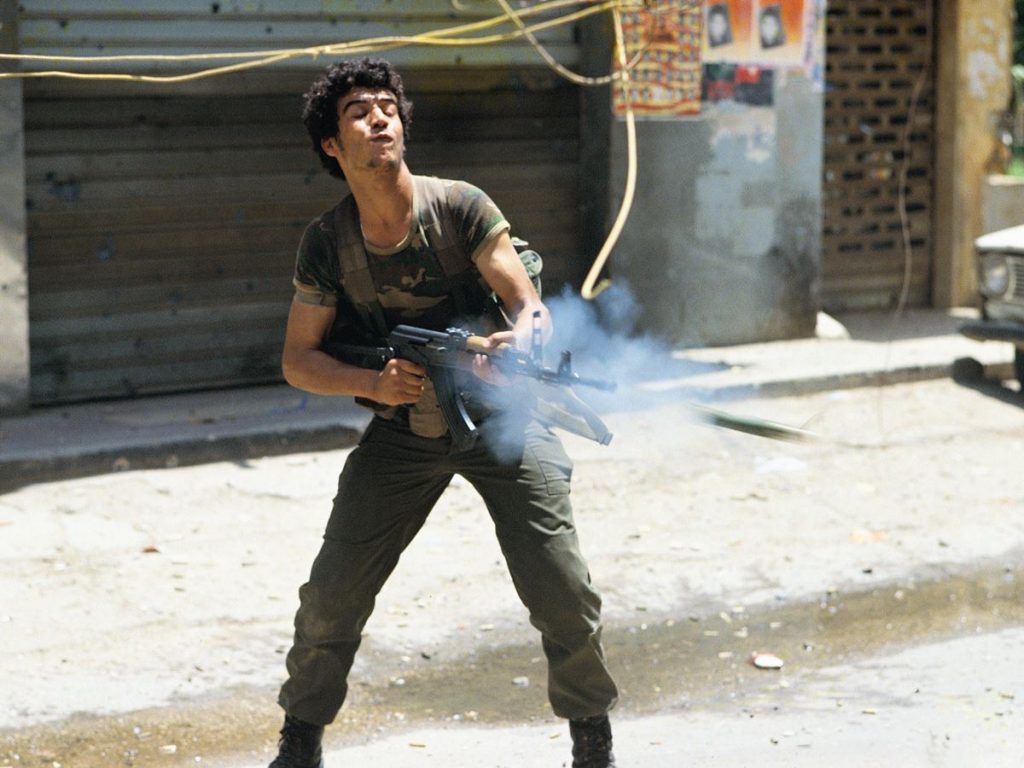

Aral’s photos from the Lebanese civil war made the covers of international magazines countless times during the 1980s. I ask him to relate a scene that stuck with him from that incredibly complex civil conflict.

“Where do I start? I was in the South of Lebanon, in Nabatieh. We were walking along with many journalists on this dirt road. It was July or August, I can’t remember. Dry time, anyhow. And yet the road was muddy. I bent down to see, I saw the mud was blood. There were bones in that blood, pressed under tank tracks. The dogs would come to eat off the mud. The Israeli tanks had passed on top of the dead bodies and crushed them to the ground.”

“The day of the massacre in Sabra and Shatila, I was in Istanbul. I returned to Lebanon the very next day. I did not get to see the mounts of dead bodies, I only captured the funerals of the slain Palestinian refugees. But I did see another massacre, perpetrated by the Shi’ites –the 6th infantry brigade, together with the Amal Movement and the Syrian Army: they were killing refugees for one year, non-stop. They must have murdered thousands.”

Aral was in Lebanon from the very first week of the bombardment of Beirut, when the Israeli army were on the offensive from land and sea. He remembers the city as a dark, vast landscape of void.

Maybe if women got autonomy within the family, if they became independent, things would change.

“One day, I take the picture of a civilian, a woman holding a baby, running amid ruins. You must understand, at those times we were not accustomed to the media flooding us with scenes of war affecting civilians, like we see today in Syria. There was no live footage from the ground as such. My picture made the cover of TIME magazine.

A month later, the TIME offices were inundated with letters addressed to me saying ‘we thought the Israeli army was attacking only terrorists, we didn’t think civilians were affected’. There was genuine distress in those letters. And yet, years after the photo was taken, nothing had changed. The war continued unabated, civilians kept dying every day. Same thing with the picture of that little drowned boy, Aylan Kurdi, who made the headlines in September 2015: he was seen as the epitome of the refugee drama. Three years later, and what’s happened? Absolutely nothing. Do you understand what I am saying?”

For a while, as we are talking to each other over steaming cups of soup in Istanbul, he says nothing. He asks me why I am not eating; I tell him some stories make eating almost impossible. He smiles.

“Are you surprised? I saw what the Israeli army’s cluster bombs did to children. But who made those bombs? The U.S. of course, but also Sweden, Greece, Turkey! When I was covering Rwanda, we came to a refugee camp in Tanzania and I saw the Red Cross; it was a huge camp.

It was there that I heard that the first seller of weapons to Rwanda was Belgium. In Afghanistan, I saw people being blown up by Swiss-made anti-personnel mines only to be taken to hospitals operated by the Swiss Red Cross! You want a more recent example? Look what happened a few weeks ago: after the Khashoggi murder and the exposure of the famine in Yemen, Norway announced that they would stop exporting weapons to Saudi Arabia. Excuse me for asking this, but did they think it was alright to export them before?”

Not really eating, I ask him why he thinks brothers fight brothers.

“It’s ego,” he says without faltering, surprising me again.

You know what Marx said about religions: they are the opium of the people.

“Ego and hormones. Kurds and Turks have been living side by side for a thousand years. But if you look at the past, you will see only blood: everybody attacking everybody. Peace needs one thing: forgetting about revenge. Teaching your kids not to kill in the name of some past injustice.”

He stops for a while. Then says:

“Maybe if women got autonomy within the family, if they became independent, things would change.”

Women?

“Yes. Only women can stop the cycle of vengeance. Teach their kids better. But in Turkey and the Middle East women won’t stop using the language of war. They do not refuse, do not resist the feudal system of honour and ego and revenge.”

I dare counterpoint that it is probably not very easy for women to stand up to men in those areas.

“No! It is easy. I saw it happening in Northern Ireland. In Rwanda I saw people asking for amnesty for their worst enemies. In Nagorno-Karabakh I saw Azeri women who had lost their children to war, rallying for peace. And then I saw others, who had lost no children to war, asking for more blood, not letting go of the past.”

One of Aral’s most impressive pieces of work is a series of photographs about religious fanaticism. He shows me pictures of self-flagellations from the Philippines:

“You know, everyone does the same. Hindu, Buddhists, Christians, Muslims… I once made a documentary about the religious rituals in 25 different Muslim countries. It was broadcasted on Turkish TV; it is banned now. Anyway, do you know what everyone kept saying? ‘Our version of Islam is the best!’ Whether in South Africa, or in the Philippines with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, or in Afghanistan –I was there on the brink of the war with the Taliban, with Rashid Dostum– everyone said: I am right! My Islam is the best!”

Travel! Take your backpack and travel the world.

“Well, Coşkun,” I say, “it seems to me that it’s not only ego and hormones that drive people crazy, but religion too, no?”

He thinks it over for a while.

“You know what Marx said about religions: they are the opium of the people. But opium is a drug, a medicine in some ways; like Aspirin. If you use Aspirin for fever or headache or for your heart, then it is ok. But if you have diabetes, you can’t use it. Religion is like that: it’s good for some things; but not for everything. Years ago, I asked the Dalai Lama about the plight of the Rohingya in Myanmar. He said that the people perpetrating this genocide where not true Buddhists. Yet if you ask them, they’ll tell you that the Dalai Lama is not a true Buddhist! Who is right? When I talk to my fellow Turks and they say they want to follow Islam, I reply: sure, but which one?”

There I had it then: here was a man who had seen everyone killing everyone, in the name of every religion, state affiliation, ethnicity, nationality, and tribe you can imagine, a man who had lost all belief in ideologies and collective groupings, retaining only a love for individuals, for human beings as such, and a deep-seated faith in the sensitivity of women and their potential aversion to hurt and war. So what would such a man advise the youth of this world to do?

If you want to build a future for a country, you have to build it for everyone.

“Travel! Take your backpack and travel the world. Talk to people. Ask questions. Do not take all your information from books: ask and learn. That’s the only way to learn empathy. The only way to understand that what you read in your books and who you see on your screens are real people. It is the only way to understand that your perceived enemies are people too. For example, yesterday I came back from Israel after having been away for 16 years.

Back then I was slightly optimistic for the future of Israelis and Palestinians. But not anymore. Because now I saw that Palestinians have changed too: there are rich, strong, intelligent people in the Palestinian Diaspora who, whenever they get fresh news from the ‘home country’, they feed it right into the discourse of revenge. It reminds me of the Irish diaspora, in America, who used to funnel money and arms to the I.R.A.”

“Again, I must tell you about the role of women in stopping this desire for vengeance. I was in Sweden, 2 years ago, and I visited houses of Arab and Kurdish origin. In the Arab houses people would talk about the future, their kids’ schools, how their life was going to change for the better. In the Kurdish houses, it was all about ‘the old country’, all about revenge: “they must kill them, they must break them [Turks]”– that was the adage.

This talk is beyond dangerous. If you want to build a future for a country, you have to build it for everyone. In Turkey, this means for Turks, Kurds, Armenians, Laz, Georgians, Yezidis, everyone. You can’t say these people must avenge those people. You can’t say these ones are victims and those aren’t. Everybody is a victim.”

In 2015, after the Kurdish forces had recaptured Kobani from ISIL and the Kurdish-led HDP had made great gains in the Turkish national elections, Aral told his wife and kid he was going to Diyarbakır to celebrate the New Year.

“I had a good feeling, I wanted to experience this new sense of freedom. But when I arrived, I cried and I cried for two whole days. Diyarbakır, you know, is two different cities: a modern one with tall buildings and malls and things; and an old one, the poor side of town, inhabited by the Kurdish diaspora of the 1990s, the people internally displaced after the Turkish government wiped more than 3,000 villages off the map.

You asked me why brothers kill brothers. It’s vengeance. It’s stupid.

What I saw when I arrived in Diyarbakır was fires burning and bombs exploding in the old parts of the town, when on the other side it was simply business as usual. You could sit and sip your cappuccino on the main square and hear the bombs go off, smell the fire, see the smoke! I said to myself: where is the solidarity between the Kurdish people? I met a series of young girls, 16-17 year olds, who were fighting for the PKK. They told me they were being paid to do so.

I met young men who had graduated as teachers and, having to wait years for their appointment, signed up to the Police for the (extraordinary for Turkish standards) monthly wage of 3,000TL, and were posted directly to the sniper shooting areas on the border. I saw a dozen of them get killed in a single week. I talked to a PKK guy who said that the violence that spilled over the Turkish border at the time was revenge: Erdoğan had promised too much and delivered nothing. It was insane…”

He bows his head, not in sadness, but in quiet wisdom, I think.

“It was the same story in Belfast, in 1981. I met this guy who was an American and had come to fight for the IRA. His family had been killed by the Protestants and he had come to extract revenge. You asked me why brothers kill brothers. It’s vengeance. It’s stupid. But it’s the easy way out.”

Kommentarer