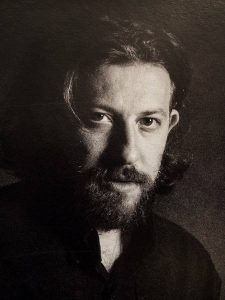

Enri Canaj is the latest addition to the legendary Magnum photographers’ crew. His migrant family’s history infuses his award-winning photographs with delicate sensitivity.

“What I remember most from our crossing over to Greece, were the lights: they were so many, so bright, it was incredible!”

That was 1991. The 11-year-old Enri Canaj was leaving his native Albania to begin a new life in Greece, just before the collapse of the Ramiz Alia regime. His middle-class parents – his dad, a worker in a tractor factory, his mom working in a bakery – had managed to secure one for the very first, very rare tourist visas that allowed Albanians to exit the once-inaccessible fortress built by Enver Hoxha. They wanted to see what was “out there”, what kind of life they had been missing all these years.

Without realising it, my dad had booked us into a hotel were prostitutes would spend the night.

26 years later, Enri Canaj is the latest addition to the legendary Magnum photographers’ crew. His migrant family’s history infuses his award-winning photographs with delicate sensitivity: images of refugees struggling with the waves in the Aegean Sea, love stories among druggies in central Athens during the crisis, the drama of stranded souls in refugee camps across Europe.

“I am an immigrant myself, trying to record immigrant life,” he says.

“I cannot look at these people unenthused, professionally. In some way, I have also experience what they experience. They know and I know that we have gone through the same things. So I talk to them straight; I look them straight in the eye.”

“The first night we arrived in Athens, my dad was trying to find a hotel right in the centre. So we fall asleep and next morning I wake up to the spice smells on Evripidou Street and the thousands of people on the streets, out to shop. I only saw the girls first that afternoon: they were getting dressed and applying make-up with their doors open. Without realising it, my dad had booked us into a hotel were prostitutes would spend the night, before going out to the streets to work. I remember those girls: how tender they were towards me and my sister, how beautiful they looked! They even gave us pocket money! We stayed in that hotel for about a month, before moving to a house we found in Colonus, a neighbourhood packed with immigrants like ourselves, back then.”

In Sophocles’ tragedy, Oedipus at Colonus, the blind king Oedipus, exiled from Thebes, reaches Colonus, accompanied by his daughter Antigone. The Athenians feel great pity for the condition of this once great king, but do not welcome him in, fearing the curse he might be carrying with him, after having (unbeknownst to him) murdered his father, Laius.

In Colonus, the Canajs occupied a room around a central courtyard, together with dozens of other families from Albania:

“Others had managed to cross the borders by themselves, others had brought their families along; others were young couples that would fight long into the night about their common predicament. It was like the migrants one sees today: some tag their kids along, others are just a group of young boys, still others are so alone.”

“I remember how unwelcome I often felt those early years (1992-1993): the police would stop me all the time to check my papers and, having none, I would end up spending the night in jail at the police station, a 12-year-old kid, until my parents got me out the next day.”

When you emigrate, you often build defences to help you against the racism you experience.

With its characteristic bureaucratic rigidity, the Greek state only granted the Canaj family leave to stay after 9 whole years. When Enri applied for the Greek citizenship, some years later, the official in charge asked him wither he knew of any Greek poets. Enri replied by quoting the first line of C.P. Cavafy’s Ithaca, (“As you set out for Ithaca, hope the voyage is a long one”), stunning the official.

“Like Ulysses, I wanted to wander to other cities, gain new knowledge, new experiences. Cavafy’s poem is incredible. I have two nationalities that occupy equal ground within me, but I mostly feel like a citizen of the world. No matter where you come from, there will always be other countries you can love and claim as your own.”

But what about coming back home, Ulysses’ ultimate goal? His reply comes through the tragic story of a Syrian refugee he met in Athens:

“We were having dinner at a friend’s house, and the man sitting next to me started telling me his story with such candidness that I simply froze. Both his parents and his twin brother had died in Syria. He showed me a picture of his dead brother and said that, for a whole year after his death, he was unable to utter a single word. He was in that much of a shock. How can you stay put when all you had has been destroyed, when everyone you’ve loved is dead? Yet, when I asked him whether he ever wanted to go back, he said yes. Everyone’s answer is a resounding yes.”

I look at immigrants and I see in them the entire tragic, human condition.

Enri often goes back to visit Albania.

“I step off the bus at Tirana and it smells like home. I travel back in time, when I was a kid. When you emigrate, you often build defences to help you against the racism you experience, the difficulties in your way, and I built inside me this imaginary, exotic world that meant ‘Albania’.”

Enri grew up in Tirana, with his grandparents, until he was 5 years old. His granddad was quite privileged: the Albanian government had granted him one of the very few television sets going around; their house was in Blloku, the government quarter, only a few places down the road from Enver Hoxha’s residence itself. Every time he and his grandmother would stroll down the street, the old lays would admonish him: Look straight ahead, don’t turn your head.

“Under communism everyone had a job for the State and everyone stole from the State, in order to survive. You’d pinch things from your job and then exchange them with someone else’s stolen goods,” remembers Enri.

In the piece he recently had in Le Monde, where he records life in today’s post-communist Albania (“a piece I always carried within me”), he incorporates in his photographs many fantastic elements from his own memories as a child.

“I remember when things started getting really bad, under Ramiz Alia. People would line the streets, waiting for a piece of bread that was not always available, in the end. Albania is now a much more optimistic country, but it has nothing in common with the country I left behind. It is way harsher. Even our language is different now: there are so many words and phrases that my parents would be hard pressed to recognise.”

“I didn’t want to provide simply a record of events”, he says when we start to talk about refugees and immigrants again.

“What I want to do is transform what I see, without changing it.”

Meaning?

“I look at immigrants and I see in them the entire tragic, human condition. So I want my photographs to be almost transcendental, to capture more than they depict. This is how I am trying to make my own, personal mark as a photographer. He recalls uncomfortable moments on the job: “In Lesvos, whenever I saw dead refugees’ bodies coming in from the sea, I wasn’t sure whether I should be photographing them or not. In the end I decided I had to photograph them, there was no other way, I had to show people what was going on. You can’t wrap a pink film around reality.”

I had nothing to lose.

He then recalls the single most shocking moment of his career so far:

“We found this nine-month-old baby on the beach, in Lesvos. It had drowned. We couldn’t just leave it there. We called up the port authority to come and get it and they said they couldn’t make it before 2 or 3 days afterwards. They were that busy carrying in other people’s dead bodies. So we picked up the little body and carried it to the morgue ourselves. I couldn’t sleep for days afterwards. People don’t want to see reality unless I push them to do so. If you don’t take that picture, you’re as good as lying.”

To survive as a teenager in 1990s Athens, Enri sold koulouria (a local type of bagel, similar to Turkish simit) in the city’s central square, Omonoia (“Place de la Concorde”) in the mornings and attended school in the afternoon. At 17, working at a furniture factory, he borrowed a book that lined the exhibitors’ shelved in order to improve his language skills by reading it out loud. It was Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha.

Photography helped me decompress all the experiences I was carrying within me.

He read it again and again after that, to make sure he got everything it said. After that, he read all of Hesse’s books in a row. And one day, he happened upon a photography exhibition and thought that would be a good way to make some proper money: to study photography and become a wedding photographer. He asked his boss to fire him, so he could use the compensation money to pay off the first-year fees. Study photography?, his boss said. You’ll be penniless! But he did what Enri asked him to do.

“I had nothing to lose,” Canaj says.

“When you are an immigrant, you can try your hand at so many things. You have this unconventional freedom to choose what you want to do, what you want to work on.”

His love affair with photography-simply-as-a-source-of-money didn’t last long. In his first month at photography school, the principle gave him a photographic album about Albania, by another celebrated Magnum photographer, Nikos Economopoulos. Canaj was inspired to bits:

“I never thought anyone could ever take such beautiful pictures!”.

He started reading books about the art of photography, interviews by other photographers, books upon books, fiction, social sciences, history: he started expanding his horizons.

“Photography helped me decompress all the experiences I was carrying within me,” he says. He stopped being a passive receptor of reality and “acquired a possibility of expression”.

He continued working odd jobs to make ends meet during his studies. Jobs that would allow loads of free time during the day – so that he could photograph “his own things” without “compromising his aesthetic criteria. He never took a single wedding photograph. He did work for a couple of years as an assistant to a fashion photographer, but that was “an intolerable, fake world” that helped him, though, realise what he did not want to do:

“In the end, one can find one’s niche by subtraction, by removing from the list what one does not like doing.”

And then, a photographic competition entitled “Athens: the changing city”, run by the British Council in Athens and the Institute for Migration Policies, got him into a workshop run by no other than Nikos Economopoulos himself, the man who had inadvertently changed his whole attitude towards photography.

These people lived in the neighbourhood I had grown up in, their haunts were familiar to me.

“I learnt about that competition by chance, dropping by my old photography school one day. I sent my application in on the very last day. And they said yes!” And when that workshop was over, the student album printed, and their pictures had been exhibited in different countries, Enri Canaj’s career as a professional documentarist photographer took off the ground.

He started working for Greece’s most prestigious newspapers and magazines: Tahydromos, Ta Nea, Kathimerini (for whom he still works today and through which we met each other). In his spare time, he still ran his own photographic projects:

“For 3,4 years I systematically took pictures of couples that were both junkies, living in the centre of Athens. It was a difficult, tiring job: these people lived in the neighbourhood I had grown up in, their haunts were familiar to me. From 2010 it became obvious that the situation was changing rapidly for the worst. My neighbourhood had become a mirror of the city centre’s complete collapse. Thousands of shops had been closed down, I remember the city being really, unmistakably dark. People would walk with their heads bent, sulking, murmuring, or silent. Things are a little better now, but I think it’s only because people got used to living this way. Athens is now changing in the way other metropolitan European cities are changing: where family ties protected you once, people have now become distance, isolated, alone.”

And how do these isolated people see migrants and refugees trying to come into their country?

“What all immigrants look for is a safe place to live in. For us Albanians, moving to Greece was relatively easy: things were familiar here, the food, even the language was familiar to our ears. An Afghani or Pakistani child has much greater difficulty assimilating the nuances of Greek or European culture. And the older one is, the more difficult it is to integrate. You must try joining in, of course, but there needs to exist some basic, necessary help. I remember we integrated into Greek society entirely through our own efforts. There was no programme, no framework we could use.”

There are times when you want to let the camera drop and try to digest what you have just witness.

And what about Europe? Enri Canaj has photographed refugee camps and housing complexes in France, Germany, and Italy. He recalls villages close to Leipzig or Dresden, places where “one dies of boredom”. He calls to mind “huge, communist blocks, scary building, brooding people that were out of place, put there as if on purpose.”

He had gone to Germany to photograph Syrian ex-refugees in their new homelands.

“I remember this cloud cover over my head; not a single ray of light stole through. You must understand, these people come from places where the sun is a nourishing source by itself. I felt like I could not breathe. The locals had never seen refugees before. I kept hearing stories about knocking on Syrians’ doors, wanting to throw them out of their houses, threatening to burn them down. Sad stories.”

Enri says that Greeks have been amiable towards refugees so far because none of the refugees want to stay in Greece. They were only seen as potential threats by other Europeans. But now that Europe has started closing its doors to new arrivals.

“I see people becoming harsher towards refugees, day by day, in Greece and everywhere else. It’s as if the locals have had enough. But when someone comes to you from a war-torn country, you cannot just shut the door on his face saying enough, no more.”

Refugees’ stories are so shocking, Enri says, that you can’t but see look at them with all the tenderness in the world – echoing the way he talks about the prostituted he had met as an 11-year-old child in that hotel in central Athens:

“When you grow up in places like that, you understand that people are not dangerous, they are tender, like all of us. It is circumstances that have made them take up these jobs. One must look at these people with the respect they deserve.”

Once his project on photographic refugees was over, he locked himself at home, drew down the blinds, and refused to leave the house for a month. He had amassed such great psychological pressure, carrying it inside him from one camp to the next, that when the project was over, he simply collapsed.

I never imagined that one day I would be working for Magnum.

“There are times when you want to let the camera drop and try to digest what you have just witness, so that you can move forward yourself.”

But not only Germans and not all Greeks – not all Europeans – are racists, he says. Racism is definitely on the rise, but the state itself – in Germany at least – offers these people jobs, a home to live in, a chance for a better life.

“The arrival of hundreds of thousands of refugees is a historical change for Europe. I believe that humanity will prevail, that their presence will grant Europeans greater tolerance for those who differ. There exists another Europe: the Europe of freedom, the Europe of opportunity.”

For his latest personal project, he tracks a family of Afghan immigrants who tried reaching Germany, via Hungary, just before the borders to the north of Greece were shut down.

“There was this mother and her two kids and their grandmother. They were involved in a terrible road accident in Serbia. The mother had had to have both her legs amputated; one kid came out unscathed, but the other one had to have a metal plate inserted in his leg. The grandmother – her daughter’s only support – died in the crash, even though no one told them until later.”

The family was taken to a psychiatric clinic in Serbia. That’s where Enri met them. They stayed in there for a whole year.

“Within a few months, the children had learnt to converse in Serbian and they had learnt by heart the names of all the patients. Very recently, Sweden decided to help them out and granted them asylum. The mother started smiling again only a month before their departure for Sweden. I remember the kids, how they looked upon everything as if it were a game. I believe they knew exactly what was going on, what kind of an institution they were in and what sort of patients their friends were, but they had found their own way to deal with the situation. They reminded of myself, when I had first migrated to Athens.”

My parents never understood what I exactly do with photography.

Enri is on his way to Sweden next month, to track the family down and complete their story.

And what about the success of having been selected to join the Magnum team? What does he make of it?

“I never imagined that one day I would be working for Magnum; but you know what they say, each has their own, silent dream. If you continue believing in yourself and you focus on your art, you always end up in a good place. I did not know that place would be Magnum, I guess one needs to be lucky or at the right place, at the right time too. Being selected to join such a team is a very difficult process: your work needs to be recommended and eventually voted for by hundreds of world-class photographers, each with their own line of work, each with their own selective vision. The evening I heard the news, I didn’t sleep a wink!”

And what about his parents? Are they proud?

“My parents never understood what I exactly do with photography, or how I do it. They were very busy working at all times, to be able to feed my sister and I. But their nonchalant stance towards professional photography sheltered me from becoming full of myself. I was always grounded and timid about my work.”

I have never been afraid, I don’t think I have that sentiment within me.

Until a cousin of his Albania met up with a Greek journalist from the Greek state news agency (APE-MPE) and asked whether he knew her cousin.

“I don’t know of anyone in Greece who does not know who Enri Canaj is!” he replied. And now, his proud parents cannot get enough of friends and family calling to say that they saw his work or his awards on some newspaper or on TV or in the social media.

And has he ever felt fear on the job?

“I have never been afraid, I don’t think I have that sentiment within me. I feel protected by the energy I have amassed working and living in tough neighbourhoods throughout the years: I can talk to anyone, be friendly with the most difficult people you can imagine. They let me. It’s as if they feel the streets on me. You see, I belong to all the people I have ever met, all the people I have ever photographed. Above all, I am a migrant. And migrants feel like they have nothing to their name, they carry nothing, they are free. You can try your hand at anything then, because you have nothing to lose.”

Kommentarer