He was a hunter of light and shadows. He was a king, in palaces, slums, and art circles.

“The history of the world is the sum of the lives of the everyday people, the atoms of this world. And it is this magnificent world that Ara Güler wanted to preserve.”

– Bishop Sahak Maşalyan, in Ara Güler’s funeral on October 20th 2018 in Istanbul

About eight years ago, I was asked to write the post-face to the Greek translation of David Boratav’s novel “Murmures à Beyoglu”, the story of an insomniac French Londoner who returns to the city of his father in an effort to cure himself by a sort of psychological repatriation.

I was myself living in Istanbul back then, and jumped at the opportunity of documenting the way the city was transforming itself as quickly and vortex-like as the Bosphorus currents. From favelas to concrete apartment buildings, and from pastures to skyscrapers, the city that straddles two continents was unfolding and expanding to embrace the millions of new people swarming towards it.

He was born here, grew up here, he knew how to capture its most remarkable corners at the most remarkable hours.

Today, the unofficial number stands at 22 million inhabitants. Back in 2010, there were only two bridges over the Bosphorus and one of them had not yet changed its name to the “July 15 Martyrs’ Bridge”, one among the many victims of the current administration’s mania with aggressive, political symbolism. Today there are three bridges. And two underground tunnels. And about a hundred mosques and a thousand skyscrapers to boot.

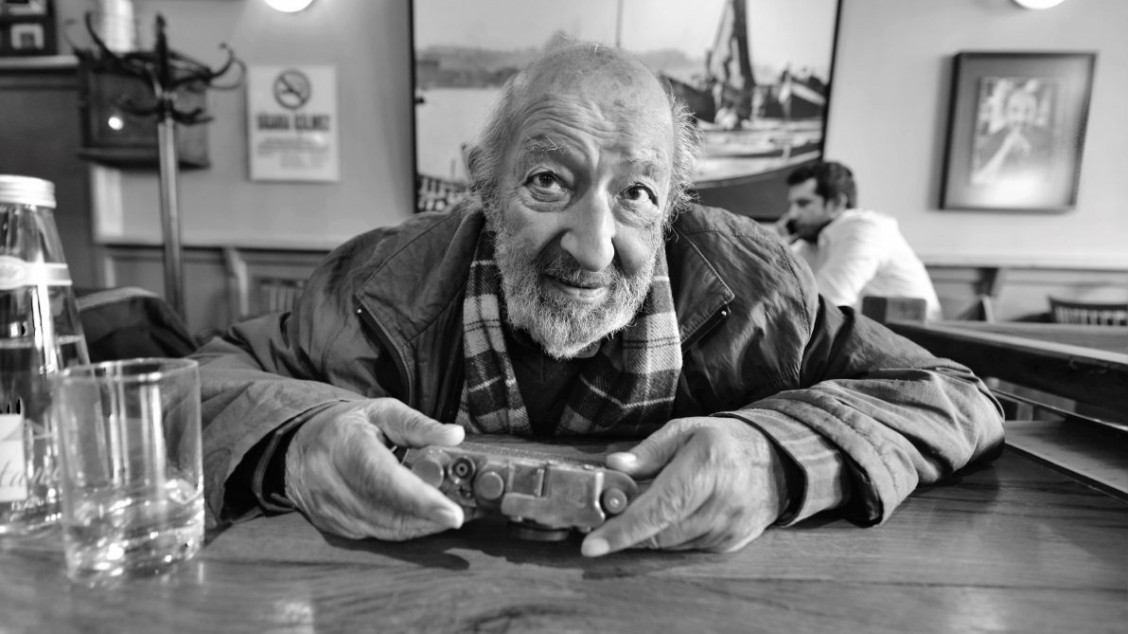

So I can only imagine what this beautiful, enchanting city must have been like when Ara Güler, the world’s most famous Turkish photographer, who passed away at 90 years of age on October 17th, was setting out to record its everyday people, its mornings and sunsets, for eternity.

When the population hardly stretched to 2 million people and was still replete with Jews, Armenians, Greeks, Assyrians, Albanians, Bosniaks, and other minorities that were either expelled, left voluntarily, or have by now been completely assimilated to the main Turkish population.

Thankfully, Ara Güler’s most important contribution to history and photography is his incredible record of this now vanished world: the 2-mllion-plus black-and-white archive of images whose protagonist is a city that has changed beyond all recognition.

He knew this town like the back of his hand.

The archive is now part of the recently opened Ara Güler Museum, in Istanbul’s Bomontiada, a renovated beer factory turned social-and-art space.

“Ara hid in his photographs the memory of this town,” says to me Nazan Ölçer, Turkish art’s grande femme and director of the Sakıp Sabancı Museum.

“He knew this town like the back of his hand. He was born here, grew up here, he knew how to capture its most remarkable corners at the most remarkable hours: the fishermen, the porters by sunrise. Unlike orientalist photographers of the 19th century, who were looking for misery, for poverty – because that was the Orient for them– Ara set out to document the working people, the decent people, the long-forgotten city quarters, the narrow streets, the up-and-down hills. I have lived my whole life in this town and if I look at his pictures, I see my vanished childhood, my younger years.”

Ara Güler was born in Beyoğlu, Istanbul, on August 16, 1928. His father was an Armenian pharmacist; his mother owned loads of properties in the neighbourhood: the Ara Café, named after him, and his favourite hangout during the final decades of his life, is housed in one of them, just opposite the historical high school of Galatasaray on Istiklal Caddesi.

I think he thought they saw his photographs just as a source of money.

It is here I meet retired businessman Melih Berk, a close friend of Ara’s for the past ten years, on the morning of Ara’s funeral.

Melih and his wife are kind enough to escort me to the inner sanctum of the event, where only family, close friends, and state and local officials are allowed to enter. A huge banner of Ara’s portrait overlooks this cordoned-off corner of Beyoğlu, carrying the words Goodbye grand master, we will never forget you.

A stage has been erected underneath, on which Ara’s coffin, covered with the Turkish flag, arrives and receives the greetings and blessings of friends and family. We have about thirty minutes to talk before I must leave to catch my plane back to Greece, and Melih has to follow the funeral procession to the Üç Horan Armenian church, and from there onto Şişli cemetery.

I only photograph human beings!’ he complained.

“I am not sure he was happy that Doğuş Group bought his entire archive”, Melih ruminates.

“I think he thought they saw his photographs just as a source of money. I remember when Doğuş was erecting this big development by the seaside, in Dolmabahçe, and they had put up big photographs of his in order to hide the construction going on behind them. Ara was passing by in a car and he saw that one of his pictures had fallen down, allowing a glimpse of Top Kapı palace to sneak behind the wall of photographs. He was so happy! He said it looked so beautiful: his pictures and then the palace sneaking in. He was always looking at the world as if through a camera lens.”

Güler was recruited for Magnum early in the 1960s by none other than Henri-Cartier Bresson himself. He amassed an impressive collection of photography awards throughout his long career, including Master of Leica and the Lucie Award. But he was above all that. When he was given the Presidential Culture and Arts Grand Award by Turkey’s president Abdullah Gül in 2005, he joked that he was enough known already; all these decorations and awards were entirely unnecessary.

“He would always correct you if you tried to call him an artist. He liked the term photojournalist. He was proud to be ‘just a photographer’,” recalls Nazan Ölçer.

“I remember we met 40-45 years ago, in the early 1970s. We were having a carpet exhibition at the Museum and he came to photograph the carpets. It was the first time he was photographing carpets and he was furious! ‘I only photograph human beings!’ he complained,” says Ölçer with a chuckle. “Of course he was the greatest photographer of portraits. But how lovely those carpet pictures were too!”

He had an insatiable curiosity, he was kind of an explorer,

War correspondent, documentarist, and fellow Magnum photographer Coşkün Aral says to me from Iceland:

“I saw Ara’s photos in LIFE Magazine in Turkey when I was teenager, living in a small town in the southeast part of the country. I dreamt meeting him one day. I came to Istanbul and worked as a photojournalist and one day, in 1972, I hopped into a trolleybus he was also riding! But I was too excited to speak to him. Eventually, after I had managed to make a name for myself shooting the violent backlash to the worker’s uprising during the 1977 May 1st protests in Istanbul, Ara and I came to build a solid friendship as master and apprentice. He was my mentor, dare I say my father. I keep judging my photos through his eye even to this day.”

“He had an insatiable curiosity, he was kind of an explorer,” adds Nazan Ölçer.

“He would photograph whatever he had been asked to photograph, professionally, but then he would discover a tiny, little detail that everyone else had overlooked. And that very photograph, taken entirely on instinct, would make him famous, and the thing he depicted, important. He could catch so many overlooked details…”

I don’t understand why they did not preserve that ship.

Ölçer backs her claim referring to the only documentary Ara Güler produced in his lifetime, Kahramanin Sonu (A Hero’s End), a poetic and disturbing tribute to the Turkish warship Yavuz Sultan Selim. Originally the German SMS Goeben, she was transferred to the Ottoman Navy in August 1914 and bombarded Russian facilities in Crimea, thrusting Turkey head-on into WWI.

After the Turkish Republic was established in 1923, the Yavuz became the flagship of the Turkish Navy until she was decommissioned in the 1950s, then scrapped in 1973. Güler’s documentary captures in excruciating detail the heart-wrenching gutting of the metal beast.

“He wanted to show that film everywhere,” recalls Ölçer.

“I don’t understand why they did not preserve that ship, make her into a museum, like Aurora in Russia.” The gutting of Yavuz, we are led to understand, is the gutting of Turkish history.

It was this penchant for detail that made Ara Güler discover one of Turkey’s most remarkable ancient Roman sites: Aphrodisias. In 1958, Hayat magazine sent him to Aydin, to photograph the opening of a new dam. Story has it that he and his driver got lost and spend the night in the remote mountain village of Geyre, where Güler noticed men playing card games on the head of an ancient Greek column.

He soon realised that the village was literary built on – and with – Hellenistic ruins. He spent the following days photographing the site, sending, upon his return to Istanbul, the images to Architectural Review. The rest, as they say, is history.

Yet his own, personal relationship with History was unpredictable. His parents’ Armenian families might have been massacred, but he refused to utilise his Armenian identity as a measure of separation between himself and his countrymen.

He saw himself as the descendant of a multinational Ottoman state.

“He wasn’t what some people may call ‘a professional Armenian’,” says Heath Lowry, an old friend of Güler’s and now Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Centre for Ottoman History Research at Bahçeşehir University.

“In other words, he did not have an agenda pertaining to his origins, he wasn’t political. He saw himself as the descendant of a multinational Ottoman state. When people tried to ask him how it felt to be a minority in Turkey, he got very upset. He would say things like ‘we were here a long time before the Turks came’ and ‘we’ve made a contribution’.”

His claim is backed by Güler himself, in Osman Okkan’s documentary Ara Güler: Legend of Istanbul.

I have no thoughts to add, the camera captures [history].

“I’ve climbed on Mount Ararat twice,” says Güler, referring to the mountain separating Turkey with Armenia, which also happens to be Armenia’s symbol of national pride.

“I planted a Turkish flag there and started singing the national anthem. But before I finished singing the anthem, the flag just blew away with the wind!”

One can’t but feel this was nothing less but a sly example of fate’s poetic justice.

Yet his camera revealed all. He thought of himself as a visual historian, someone who could record history more accurately than professional historians.

“Historians include their own thoughts in their histories,” he says in the 2015 documentary The Eye of Istanbul.

The last time Melih saw Ara was the day before he died.

“I have no thoughts to add, the camera captures [history].” When the Greek and Armenian communities of Istanbul were targeted during 6-7 September 1955, their homes and shops vandalised, Güler was there, recording the lootings and the torchings for posterity.

Not without a slight sense of lopsided humour: “September 6-7 was both a tragedy and a comedy,” he recalls in The Eye of Istanbul.

“I saw all the shops being torched. Then a guy comes along, he sees a beautiful topcoat, he wants it. But there is a shop window separating him from this coat. Never mind, he picks up a rock, throws it at the window, walks into the shop, puts on a few jackets, one on top of another. He now looks hugely fat. He exits the shop with those coats and leaves.”

“Oh boy was he a great joker,” smiles Melih, despite our meeting during a solemn occasion. “There’s this picture of him from 3 years ago, when he was in hospital. There were rumours all over Istanbul that he had died. He asked Fatih Aslan, his driver and great friend for the past 25 years, to take a picture and put it on the internet: he’s doing the characteristic joking gesture that means ‘fooled you’.”

The doctors wanted to cut it but we never told him.

The last time Melih saw Ara was the day before he died. Güler had had kidney failure for the last 4 years and was receiving dialysis 4 hours a day, 3 days a week. But he kept going.

“He was hospitalised because he fell from bed and cut his forehead. The blood would not stop because of the medicine he was taking. In the hospital, they recognised that gangrene had claimed the toes of one leg. The doctors wanted to cut it but we never told him. In the end, there was no need to.”

Güler’s uncle had been diabetic and had had his own leg cut a few times. Ara had a very funny way to relate his uncle’s peculiar story: According to the Armenian church, all body parts need to be together if one is to get resurrected during the Second Coming.

But due to some hindrance with the family grave, the uncle’s body had to be laid to rest apart from the leg, which was buried in an entirely different cemetery. Ara would joke about this, saying that a dog had run away with a bone and that the day Jesus came, they would have to get the metro to go fetch that leg if his uncle were to rise again!

“He never forgot this story. On Wednesday morning, the day he died, he was not speaking. But he kept touching his leg, to make sure it was still there. I swear to you, 90% of the man’s blood flow to his brain was clogged and he would still crack jokes when he could.”

Was Ara Güler a religious man?

In the hospital, Melih and his wife put Güler on a wheelchair and took him to the restaurant so that he would get away from the stuffy atmosphere of the room. Ara got animated, started talking.

“We found a camera from a friend and brought it to him to enjoy himself. He started taking pictures and he took a picture of me and my wife. It was the last picture he ever took.”

“We are such fortunate people because everyone born here inherits 11 civilizations,” says Güler of his fellow Istanbullus in The Eye of Istanbul. He was very upset his Istanbul was gradually losing all memory of its once multinational body. He tried to preserve that memory out of instinct.

“Everybody here is Armenian, Greek, Jewish, Assyrian, Chaldean, Turkish, Kurdish, Arabic, Albanian, Georgian, Laz, Bosniak: this is Turkey’s mosaic. We are grateful for your having come today,” says Bishop Sahak Maşalyan during his tribute to the deceased, at the Üç Horan church. And then continues – in what I can’t help but recognise as a tremendously brave speech in today’s Turkey:

Some people are not content with just existing.

“Was Ara Güler a religious man? One of the problems we have today is that we are too busy with each other’s religions, so that religions have come to lose their essence, which is to create, not to lose your human brother while searching for your God. Ara Güler was baptised in this church 90 years ago and also asked that his funeral should set out from this church. During his childhood he used to visit this church with his sharp gaze and his sharp wit and he has comprehended and embraced its philosophy, which is love. So was Ara Güler religious? If piety is to celebrate the life that God created and blessed, then yes, he was. Because he appreciated every detail and twist in this life. If being religious is to discover, study, appreciate, and elevate Man, the Book of Nature, and Humanity, created by God, then you can say that he was more religious than many other people.

Some people are not content with just existing. They want to catch the light. The Master would hunt an image for hours on end. He was a hunter of light and shadows. He was a king, in palaces, slums, and art circles.”

Güle güle, Ara Güler.

Kommentarer