It took an earthquake for me to write.

It took, in fact, 6.7 on the Richter scale, hundreds of injuries on either side of the Aegean and two dead, for me to be able to sit down and write what I have known but often, as of late, forget: That what befalls them, befalls us. That when they hurt, we hurt. Even if it is they who are hurting us; even if it us who are hurting them.

They are Turks. We are Greeks. And it took an earthquake – again – for me to reach out to them.

On the day before the earthquake hit the sea area between the island of Kos and Bodrum (nautical miles of separation: 10.8- i.e. 20 kms), I had been standing, in disbelief, in front of my TV, watching the Turkish PM, Binali Yıldırım, of the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), seal the grave of what he had meticulously interred during the past few months in Carns-Montana, Switzerland: yet another negotiation for the unification of the island of Cyprus. Yesterday was the 20th of July, the 43rd anniversary of the Turkish invasion of the north, in response to a perceived threat that the military junta in Athens was planning to forcefully unite the island with Greece.

You can’t tell if the cat belongs to a Turkish-Cypriot or a Greek-Cypriot.

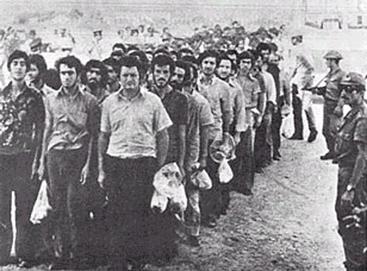

The story is well documented: thousands dead, hundreds of thousands displaced, resort cities turned to ghost towns, an island still divided. Only in the past 14 years have Greek- and Turkish-Cypriots been able to physically come together on the island, crossing the UN Green Line in Nicosia, visiting each other’s abandoned houses. And yet, here was Turkish PM Yıldırım celebrating the 43rd anniversary of this division, with a majestic military parade in the name of the 1974 “peace operation”.

The Cyprus story pains me immensely. Not because it is a story of injustice: the world is, I have come to believe, often fundamentally unjust, and politics is the art of the possible – and even less: of the feasible. It pains me because, like Northern Ireland, it is a reminder of what divides people, not what unites them. There is a video from the days after the invasion, available online like hundreds of other visual documents, that shows people dead on the streets and a black cat running in panic over them, to hide.

You can’t tell if the cat belongs to a Turkish-Cypriot or a Greek-Cypriot; it could have been anyone’s cat. And that is the point. On that day, both Turkish-Cypriots and Greek-Cypriots lost their world, their bearings and, like the confused and panicked cat, realised that the life they once knew had crumbled and vanished before their very eyes.

And then, of course, there was the falling-out-of-love with the EU.

Of course, this is nothing new when it comes to war: just take a look at Syria today. But to have anyone celebrating such a destructive event as a peace operation is a mark of callousness. And yet it should not surprise anyone that a high-ranking official of the Justice and Development Party is using division for political gain: just look at Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who divided his own country and turned Turk against Turk, Turk against Kurd, Kurd against Alevi, and Turks against everyone, in order to fulfil his ambition to become the single most important ruler of the Turkish Republic since Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

How Erdoğan has crushed the spirit of the opposition inside Turkey is, especially lately, well reported: hundreds of thousands of teachers, university professors, and civil servants have been dismissed; thousands of journalists, army members, and members of the judiciary imprisoned; the media has been muzzled and threatened. His erratic behaviour outside of Turkey has also been splashed across international media: in 2010, he had a spectacular rift with Turkey’s long-time NATO ally, Israel, accusing it of unlawfully landing on a Gaza-bound flotilla and killing 9 Turkish activists on board. Israel responded by invoking international maritime law on blockades and accusing Turkey of secretly supplying weapons to Hamas and running a media stunt.

Turkish aircraft violations of Greek air space are an everyday occurrence, yet no planes are, thankfully, downed.

The world was largely sympathetic towards Ankara, until Can Dündar, journalist and chief editor of Cumhuriyet, one of the few opposition newspapers left standing in Turkey, released photographic proof of another one of Ankara’s “peaceful and humanitarian” operations, a weapons shipment bound for the Islamist Syrian opposition. Dündar printed the picture on the front cover of Cumhuriyet on May 29th, 2015. He was arrested and imprisoned.

Then, it was the whole Russia fiasco: On November 24th, 2015, a Turkish F-16 fighter jet downed a Russian warplane conducting a combat mission in Syria, alleging that the Russian Su-24 bomber had violated Turkish airspace for 17 seconds. Russia denied it. To Greek ears this sounded wonderfully ludicrous: Turkish aircraft violations of Greek air space are an everyday occurrence, yet no planes are, thankfully, downed.

If you go on summer holiday to Lesvos, you might get to see some of the chases happening above your head from the comfort of your very own beach lounger. Erdoğan had been a staunch critic of President Bashar al-Assad from the get-go of the Syrian civil war, and so it was with great interest that the world watched him – under the pressure of terrorist attacks by Kurdish guerrillas, an enormous influx of Syrian refugees, and growing acrimony with the EU and the United States – leave his hard talk and tug-o-war behind and become Vladimir Putin’s best chum in support of the Syrian government. He even apologised. To the man who had accused him of backstabbing, “carried out by the accomplices of terrorists.” (The Guardian, Nov 24th, 2015).

But Ankara’s most powerful man seems to think of the EU nowadays as more of a headache than a worthy goal.

And then, of course, there was the falling-out-of-love with the EU: the man who everyone in Europe once thought would bring his country out of its dictatorial, military past and into a more tolerant, democratic future, has succeeded in effectively freezing Turkey’s decades-long bid to join the EU. Erdoğan, who was hailed for abolishing capital punishment in 2004, is now vowing to reinstate the death penalty “without hesitation”, as a response to the failed military coup of 2016.

Reinstating it would, of course, automatically frieze Turkey’s bid. But Ankara’s most powerful man seems to think of the EU nowadays as more of a headache than a worthy goal: he recently accused Germany and the Netherlands of Nazi practices because they refused to allow AKP politicians to speak in supportive rallies in the run-up to the referendum that would grant him immense executive powers.

Turkey’s willingness to reinstate the death penalty– and hence violate the European Convention of Human Rights – was one of the reasons Greece refused, in January 2017, to extradite eight Turkish officers who sought political asylum the day after the failed July coup.

The men – who landed illegally in Greece on a military helicopter, asking for political asylum and saying they feared for their lives – where granted the right to stay on January 26th, 2017 by Greece’s Supreme Court, on the grounds of the European Treaty of Extradition, which forbids extradition for political or military crimes if those crimes are punishable by death, or the accused are at risk of torture, inhumane treatment, grievous bodily harm, or an unfair trial, and which both countries have signed.

Erdoğan and the AKP have managed to turn friends into non-speaking acquaintances.

The Turkish government angrily accused its Greek counterpart of politically motivated scorn, even though the Greek government itself (which cannot overrule decisions of Greece’s highest court) was much more sympathetic towards Ankara’s request than the Greek judiciary. A few weeks later, and on the run-up to the referendum, Turkey was openly questioning the 1923 treaty of Lausanne, which has defined Greek-Turkish borders ever since the founding of the Turkish Republic, accusing Greece of ‘occupying’ 18 islands in the Aegean and threatening with a flash military takeover. (For the record: the Kemalist opposition, CHP, has a long record of such provocations, which is one of the reasons why Greece was initially happy that Erdoğan assumed power in 2003, thinking that this would stop Ankara’s habit of exporting internal tensions to the Aegean.)

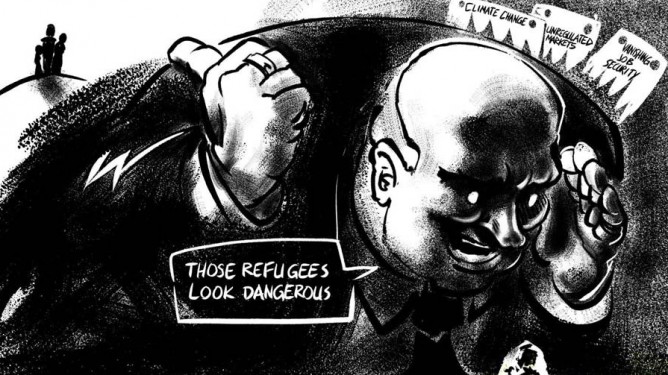

Erdoğan and the AKP have managed to turn friends into non-speaking acquaintances, allies into potential enemies, solutions into problems, plurality into a nuisance, and fifty percent of the Turkish electorate against the other fifty percent. This doesn’t get lost on the Greeks. It doesn’t get lost on anyone. Of course, exporting domestic tension is a political move not unseen in other countries. But it is still a sad one. Because it means that enough people inside Turkey suffer in discontent that the executive would rather export its vexation than allow democratic channels through which dissidents could question it.

It was only with the earthquake that I was reminded of what I’ve always known: we inhabit the same space; we suffer together.

But being on the butting end of such provocation often hinders sympathy towards the plight that has befallen Turks themselves: I have been trying to write an article on how Greeks view Turkey in 2017 for a while now, but the vocabulary employed by its government towards any foreigner that dares criticize it has poisoned my impartiality and made me forget that it is Turks (and Kurds, and Alevis) that suffer first. It was only with the earthquake that I was reminded of what I’ve always known: we inhabit the same space; we suffer together.

It was similar circumstances that, back in 1999, put an end to the unofficial cold war that was waging between the two countries since 1974. A double natural disaster triggered a remarkably enduring rapprochement, which is today nicknamed “Greek-Turkish earthquake diplomacy”. On August 17th 1999, a 7.6 earthquake hit İzmit and its surrounding areas, eventually resulting in 17,000 deaths. Greece was first on the spot to offer a helping hand, equipment, and know-how. When, on September 7, Athens was hit by a 5.9 magnitude quake (143 dead), Turkey reciprocated. And for the first time since the Greco-Turkish ended in the birth of the Republic of Turkey, Greek and Turkish people came together, ignoring decades of divisive political manipulation, united in their common misfortune and humanity.

Greeks need to be a bit more adept than usual in exercising their empathy towards Turkish people.

The political protagonists of that reconciliation are now gone from the forefront of politics: İsmail Cem, then Foreign Minister of Turkey, died of cancer in 2007; and his counterpart, George Papandreou, now leader of a party that polls less than 1% of the vote in Greece, will forever be remembered as the Prime Minister who declared the debt-ridden country bankrupt, and triggered the 2010 IMF/EU-bailout of the Greek economy that is still playing out today. Yet their rapprochement legacy continues to this day.

Unless, of course, Turkey’s strongman (or some hot-headed Greek) decides to put an end to it. In the mean time, Greeks need to be a bit more adept than usual in exercising their empathy towards Turkish people, despite their own predicament. Maybe one of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s most famous phrases – which is very often condensed to Demokrasi amaç değildir, araçtır – can help: “Democracy is not a goal,” he once said, early in his career, “it is a vehicle”; once you’ve reached your destination, you get off it. He now seems to have taken his own words at heart. And this is something no sensible person would want to wish to their worst enemy. Let alone their closest neighbour.

Kommentarer